The ancient Egyptians did not refer to their country as “Egypt.” They called it Kemet, “the Black Land,” in reference to its fertile black soil (Reidy, 2010). They referred to themselves as Remet-en-Kemet, “the people of the Black Land” (Bell & Quie, 2010), and to the Nile River as Iteru, “the River” (Collins & Burns, 2007). Their Pharaoh was called a Nisut or “king” (Asante & Mazama, 2009), their gods were called the Pesedjet or “plural of plurals” (Alford, 2004), and their ancestors were called akhu or “the blessed dead” (Taylor, 2001). Egypt was originally a name for one of their many temples (Gray, 2009),1 and pharaoh was once the name for a king’s palace (Allen, 2010).2 Referring to the civilization as Egypt and to its rulers as Pharaohs, then, is like referring to the United States as “the First Church of the Nazarene in Dallas” and to its Presidents as “White Houses.” The terminology we use for ancient Egypt today is not Egyptian, but Greek.

The Egyptians believed the entire universe was alive and imbued with spirit. Everything in nature—including rocks and plants—was believed to have both a soul and a “spirit double.” While the soul was what gave a thing its unique personality, the “spirit double” was a second body that existed in the spirit world. It was like an invisible doppelganger that accompanied a person throughout her entire life. When she died, her soul was thought to go to the Otherworld while her spirit double remained with her corpse and became a ghost (Ruiz, 2001).3 The Egyptian religion likely began with people leaving offerings of food for the ghosts of their loved ones, which was thought to keep the ghosts alive and happy. Without nourishment, a ghost would either fade away or become a demon and terrorize the living (Teeter, 2011). It was therefore important to remember the deceased, to visit their graves, and to honor them with gifts.

Just as plants, animals, and people had souls and spirit doubles, so did the earth, the sun, the moon, and more abstract forces like fertility and death. The souls of these forces were the various gods and goddesses of the Egyptian faith, each of whom had multiple spirit doubles. They were not supernatural beings, but primal forces of nature that kept the cosmos in working order. They did not exist apart from nature, but were immanent and incarnate in all visible phenomena (Assman, 2010). They were beyond human comprehension, but could be partially understood through mythology and ritual. As a body of sacred narratives, mythology provided symbolic explanations for their personalities, behaviors and backgrounds. Ritual provided ways for them to be drawn down into the human sphere, where people could interact with them anthropomorphically (Assman, 2001b).

Communicating with the gods and the dead was made possible by a force the Egyptians called heka, which means “activating the spirit double” (Asante & Mazama, 2009). The closest equivalent to this term in English is magic, but not in the way most people mean. The Western concept of “magic” is usually conceptualized as the human manipulation of supernatural agencies apart from (or even against) the will of a transcendent monotheistic god. It is also used solely for human interests, having nothing to do with religion (Budge, 1934). Egyptian magic, however, was the primeval generative power that had been used to set the world in motion (Asante & Mazama, 2009). It thrived in the spiritual doubles of all physical things, and the Egyptians felt they were expected to use it by their deities (Szpakowska, 2010). While it was often used for human aims (e.g., for bountiful harvests, protection of women in childbirth, etc.), it also provided the framework for religious rituals. Rather than dichotomizing magic and religion as Westerners so often do, you might say the Egyptians considered religion to be a certain kind of magic.

The Egyptians didn’t have a specific word for “religion,” but the closest equivalent was Ma’at, which means “what is right” or “what is justified” (Gabriel, 2002). This was simultaneously a cosmic principle, a goddess, and a process. As a principle, it was the natural order of things. As a goddess, she determined the rightful movements of the stars, the transitions of the seasons, and even the times of birth and death for animals and people. As a process, upholding Ma’at meant “doing right” by oneself, one’s society, and the universe. Every aspect of life in Egypt—including the economic, political, religious, and social aspects—was focused on this concept. It was strongly believed that a person who did Ma’at would enjoy good fortune in both this life and the next. As one character says in the tale of The Eloquent Peasant: “Speak Ma’at, do Ma’at; for it is mighty, it is great, it endures” (Remler, 2010).

Morality and religion were distinguished as completely separate dimensions of Ma’at (Assman, 2008). Morality was a civil matter that only concerned how people treated each other; it had nothing to do with how people treated the gods and the dead, which was the sole religious concern (Assman, 2008). At the same time, the religious dimension of Ma’at did not include any concern for “correct” or “incorrect” theology. The People of the Nile thought the most practical option was to treat all possible deities as being real and to seek the favor of (or to avoid offending) as many of them as possible. The act of worship did not entail a commitment to any particular doctrine or dogma, but was a purely ritual activity. This has led some scholars to argue that the way of Ma’at should not be called a “religion” at all (Assman, 2008; Kemp, 1995), but there is really no better alternative in today’s vernacular.

There is a distinction between orthodoxy (“correct doctrine”) and orthopraxy (“correct practice”), however. Many religions contain elements of both, but the largest religions today emphasize orthodoxy. Jews, Christians, and Muslims are expected to follow certain moral principles and to observe certain ritual practices, but they are generally identified in terms of what they believe and what they do not believe. They speak of how they believe in only one god, how they reject all other gods, and how they accept a particular prophet’s teachings as being “the one true way” to personal salvation. Orthopraxic religions tend to emphasize what people do rather than what they believe. Practitioners may be expected to believe in certain things like divinity and the afterlife, but their personal opinions on these matters are much less important than whether they follow certain traditions correctly (Bell, 1997). Hinduism, Shinto, and Taoism are all examples of orthopraxic religions, and the ancient Egyptian way of Ma’at is much the same in principle.

The Egyptian emphasis on orthopraxy stemmed from their belief that people were once in perfect harmony with the gods during a mythical Golden Age. At that time, men and women did not have to work to feed themselves, and everyone lived and died peacefully. But people eventually became too unruly, violent and selfish, leading the gods to cease their direct interventions in human affairs. Since then, people have been forced to earn their keep in the world. There is no guarantee that everyone who is born will live, that everyone who is hungry will eat, or that everyone who dies will live again. But upholding Ma’at was a way to reverse this change. By treating each other morally, people could potentially return the earth to its former state of harmony and joy. By engaging the gods and the dead religiously, they could convince them to intervene in human affairs again. To do Ma’at, therefore, was to restore the Golden Age as much as possible. As a final act of mercy, the gods appointed the Pharaohs to rule in their place and to show human beings how to establish and maintain Ma’at on earth (Assman, 2001b).

The Pharaohs were more than just kings; they were human incarnations of the god Horus, and their job was to ensure that Ma’at was upheld throughout the land. This was a twofold occupation that required fulfilling both dimensions of Ma’at for the entire country. In terms of the moral dimension, a good Pharaoh had to enforce just laws and bring criminals to justice. He also had to ensure that none of his people went hungry, that the poor were protected from the rich, and that the entire nation was defended from foreign threats. In terms of religion, the Pharaoh had to practice daily rituals that convinced the gods to keep hearing the prayers of the people (Assman, 2008). As such, the Pharaohs were the chief priests and magicians of the land, dispensing the ability to communicate with the gods to everyone else. Some of them were women (e.g., Hatshepsut), but since they too were incarnations of Horus, they were still considered “male.” They even wore men’s clothing and were identified with masculine pronouns (Dell, 2008).

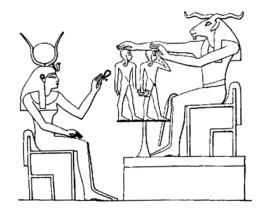

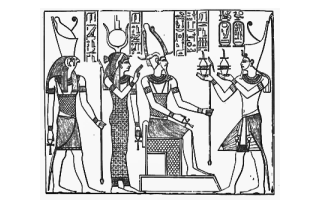

Polytheists usually worship their gods by making offerings to them, and the best offerings are generally considered to be of food. This is because eating is the single most powerful biological instinct, and for many people, having enough food to live is a constant struggle. To deliberately give food to someone else, therefore, is a demonstration of great respect. In their daily rituals, the Pharaohs first used magic to draw the gods down to earth and into cult images (e.g., statues). This was called “the Opening of the Mouth” (Almond & Seddon, 2004). The Pharaohs then recited spells to sacralize the food they had gathered for worship. When this was done, they sat down and ate, believing the gods would eat the spirit doubles of the food while they ate its physical substance (Assman & Frankfurter, 2004). In this way, the Pharaohs did not just “offer” food to the gods; they shared it with them. Having breakfast, lunch, and dinner with the gods every day was the most affectionate form of worship the Egyptians could imagine; it was like having Thanksgiving every day, only they actually ate with their gods instead of just thanking them.

While the Pharaohs were the sole mediators between gods and humans, it was impossible for them to be everywhere in Egypt at once. It was also impossible for them to perform daily rites to every single deity; if they had tried, they would never have fulfilled their more secular duties. For this reason, they deputized local priesthoods that specialized in worshiping specific gods. Each was centered in a different city with its own temple. Unlike most clergymen today, these priests did not preach, conduct public rituals, or seek to win converts (Booth, 2007). Nor did they even exist as a unique social category; most were simply appointed by the Pharaohs to serve their local temples for one month every year. What they did for the rest of the year had no bearing on their priestly functions. They conducted their rites in private sanctuaries, using the Pharaohs’ power to “open the mouths” of cult images and to share food with their assigned gods. This dispensed the blessings of those gods to their entire local populations (Sauneron & Lorton, 2000).

Most of the Egyptians were peasants who owned no land and worked on farms. When their crops were ready to be harvested and stored, temple scribes tallied their results and calculated a state tax (Winter, 2003). Collecting taxes meant collecting a share of each family’s crops. These shares were then stored in local temples, where they were used by priests as offerings in their rituals (Assman, 2008). Taxed goods and produce that were not used for this purpose were preserved for festivals (Dunand & Zivie-Coche, 2004) and for redistribution to the people in time of famine and drought (Butzer, 1984). Little is known of how religion was practiced in peasant homes, but it is known that the peasants used folk magic to protect their families, animals, and crops from evil spirits. Deities like Taweret (the hippopotamus goddess of childbirth) and Bes (a dwarf god who protected pregnant women) were especially popular in this context. The peasants also made offerings to their deceased loved ones on a regular basis; some even stored their dead in wooden cabinets or buried them beneath the floors of their homes (Frankfurter, 2010; Parsons, 2013).

While the Egyptians distinguished between “morality” and “religion,” they never made any distinction between “church” and “state” (Assman, 2008). Their state was a “church” in and of itself, and the Pharaohs were its “popes.” The intense religiosity of this civilization made such an impression on foreigners that it eventually became known as “the temple of the whole world” (Fowden, 1986). In fact, the Egyptians believed it was their own adherence to Ma’at that prevented the entire world from eroding back into chaos; the earth would only survive so long as their gods were still worshiped and their ancestral laws and traditions were still being followed. As such, the Egyptians were extremely conservative and did as little to “move forward” as they possible could. They even restarted their calendar at “Year 1” whenever a new Pharaoh took the throne (Cowie & Johnson, 2002). While it may seem easy to scoff at them for such, we must remember that the Egyptian civilization survived and remained mostly unchanged for well over 3,000 years.4

Mummification originated in predynastic times, when the deceased were buried in shallow pits in the deserts. Their corpses were naturally preserved by the heat of the sun and the dryness of the sand, but they were sometimes uncovered by grave robbers or animal scavengers. This necessitated the use of tombs instead of outdoor burials; but upon switching to this alternative, the Egyptians discovered just how quickly corpses can decompose under normal conditions. This led them to experiment with different ways of artificially preserving corpses (David, 1998b). Over time, a satisfactory method of embalming was developed and became more commonly used. The procedure was very expensive, so it was often a privilege that only Pharaohs and nobles could enjoy. Nevertheless, mummification was deemed important due to the Egyptians’ belief that a person’s spirit double could not survive as a ghost without having its physical counterpart preserved in some way (Cowie & Johnson, 2002).

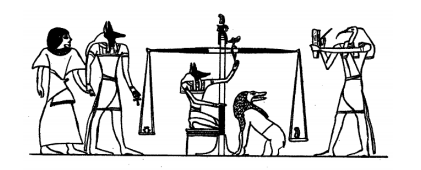

The soul was separated from both the body and the spirit double after death, and it traveled through the Otherworld to be judged by the gods. Its fate was determined by the Weighing of the Heart, which involved measuring the heart of the soul against the whole of Ma’at itself. This process is represented in funerary art by a pair of scales with a human heart sitting on one end and a feather (representing Ma’at) sitting on the other. The Egyptians believed that the heart was the seat of a person’s intellect, and that it recorded each of his or her various deeds in life. Depending on how many good or bad deeds that person had committed, the heart could be light or heavy. If it was too heavy with sin, the soul was either destroyed, fed to a demon named Ammut, or thrown into a burning lake of fire. If its heart was more or less in perfect balance with Ma’at, the soul was deemed worthy of eternal life. It was then reunited with its spirit body to become an akh or “blessed ancestor,” and it dwelled with the gods in paradise forever (Shaw, 2003).

It is often assumed that during the earliest stages of Egyptian history, only the Pharaohs and their nobles could hope to have a happy afterlife; some writers think the concept of a universal hereafter did not emerge until quite later (Walton, 2006). However, most of the people (i.e., the peasantry) were illiterate and could write nothing of their own beliefs and practices. Pharaohs were rich and had well-educated scribes to keep records of everything they did. It only makes sense, then, that most of our information about Egyptian funerary customs comes from the Pharaohs’ perspective. Even in predynastic times, peasants wrapped their dead in animal skins and buried them in fetal positions, facing west (Parsons, 2013). The sun sets in the west, and the use of the fetal position suggests a hope for rebirth (i.e., that the deceased will rise again just as the sun rises again in the east). There would have been no point in doing this—or in making offerings to ghosts—if the peasants had not believed that life after death was somehow available to everyone.

The Egyptians also believed in at least two different heavens that were separated by the path of the Zodiac, which they called “the Winding Waterway.” Beneath the Zodiac and around the constellations Orion and Canis Major was the “Field of Reeds,” which was an agrarian paradise that had sunshine, lush waters, and fertile crops. There was “ploughing therein, reaping and eating therein, drinking therein, copulating, and doing everything that was once done on earth…” (Taylor, 2010). This heaven appears to have been a place where crops were grown to provide the dead with food. The “Field of Offerings,” on the other hand, was situated in the northern sky (i.e., around Draco and Ursa Major). There is very little information concerning its qualities, but its name suggests that it was a place where rituals were carried out. It is tempting to theorize that while the peasantry worked in the Field of Reeds, the Pharaohs continued practicing their daily religious rituals in the Field of Offerings (presumably to help keep the universe in working order). Either way, the blessed ancestors who lived in both fields were thought to be capable of traveling back and forth between the two heavens and the realm of the living quite easily (Assman, 2001a).

Egypt’s decline began during the 4th century BCE, when it was occupied by foreigners. While the Greek Ptolemies tried to preserve the native traditions—even going so far as to fulfill the Pharaohs’ religious functions—the Roman emperors who followed them did not care. Without their messianic priest-kings, the people lost the core of their entire cultural system. Their priesthoods and temples fell into disrepair, but their deities continued to be worshiped privately or in Hellenized mystery cults until 392 CE, when such worship was illegalized by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. Coptic Christianity then became the dominant creed of Egypt, but was later eclipsed by Islam. Some native traditions survived, however, and were assimilated into the folk elements of these new monotheistic faiths. Even today, there is an annual celebration of the Islamic saint Abu Haggag that is clearly modeled on the ancient festival of Opet, in which the deities Amun, Mut, and Khonsu were celebrated by a procession of boats around the Temple of Luxor (Brewer & Teeter, 1999).

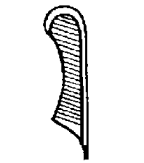

Different religions are associated with specific symbols (just as the hexagram, the crucifix, and the star and crescent are used to represent Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, respectively), and there is no better symbol for the ancient Egyptian religion than the ankh, which resembles a cross with a loophole on top of its arms. No one knows exactly what this shape represents; it has been likened to a sandal strap, a key, a wedding knot, or even the male and female genitalia during sexual intercourse (Asante & Mazama, 2009). In hieroglyphic writing, the symbol means “eternal life” and is almost always used by a god or goddess to resurrect and immortalize the dead (Guiley, 2006; Remler, 2010). The symbol was later adopted by the Coptic Christians, who called it the crux ansata or “handled cross” (Andrews, 1994). It has since been used by Western occultists and certain new religious movements. However, neither of these more recent associations is definitive. The ankh was, is, and will always be the primary symbol for ancient Egyptian culture and the commitment of its people to establishing Ma’at in every walk of life.

1 It is derived from Aegyptos, which is a Greek corruption of Hikuptah (“Mansion of the Soul of Ptah”). This was originally the name of a temple in the Egyptian city of Mennefer, which is otherwise known today as Memphis (Gray, 2009).

2 The original native form of pharaoh was per-a’a, which means “great house” (Allen, 2010).

3 The indigenous term for “soul” was ba, and the indigenous term for “spirit double” was ka (Ruiz, 2001).

4 The United States of America, in contrast, is not even 300 years old.

Alford, A. F. (2004). The midnight sun: The death and rebirth of god in ancient Egypt. Walsall, UK: Eridu Books.

Almond, J., & Seddon, K. (2004). Egyptian Paganism for beginners. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn.

Andrews, C. (1994). Amulets of ancient Egypt. Great Britain: The Bath Press.

Asante, M. K., & Mazama, A. [Eds]. (2009). Encyclopedia of African religion, volume 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Assman, J., & Frankfurter, D. (2004). Egypt. In Johnston, S. I. [Ed.], Ancient religions (pp. 155–164). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Assman, J. (2001a). Death and salvation in ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Paperbacks.

Assman, J. (2001b). The search for god in ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Paperbacks.

Assman, J. (2008). Of god and gods: Egypt, Israel, and the rise of monotheism. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Bell, M., & Quie, S. (2010). Ancient Egyptian civilization. New York, NY: Rosen Publishing Group.

Bell, C. (1997). Ritual: Perspectives and dimensions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Booth, C. (2007). The ancient Egyptians for dummies. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Brewer, D. J., & Teeter, E. (1999). Egypt and the Egyptians. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Budge, E. A. W. (1934). From fetish to god in ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Dover.

Butzer, K. W. (1984). Long-term Nile flood variation and political discontinuities in Pharaonic Egypt. In Clark, J. D., & Brandt, S. A. [Eds.], From hunters to farmers: The causes and consequences of food production in Africa (pp. 102-112). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Collins, R. O., & Burns, J. M. (2007). A history of sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cowie, S. D., & Johnson, T. (2002). The mummy in fact, fiction and film. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

David, A. R. (1998b). The handbook to life in ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Dell, P. (2008). Hatshepsut: Egypt’s first female Pharaoh. Mankato, MN: Capstone, 2008. Dunand, F., & Zivie-Coche, C. (2004). Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 396 CE. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Fowden, G. (1986). The Egyptian Hermes: A historical approach to the late Pagan mind. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Frankfurter, D. (2010). Religion in society: Graeco-Roman. In Lloyd, A. B. [Ed]., A companion to ancient Egypt. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Gabriel, R. A. (2002). Gods of our fathers: The memory of Egypt in Judaism and Christianity. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Gray, C. (Director). (2009). Out of Egypt [Television series]. Silver Spring, MD: Discovery Channel.

Guiley, R. (2006). The encyclopedia of magic and alchemy. New York, NY: Facts On File.

Kemp, B. J. (1995). How religious were the ancient Egyptians? Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 5(1), 25–54.

Parsons, M. (2013). Egypt: Priests in ancient Egypt, a feature Tour Egypt story. Tour Egypt website (accessed March 12, 2013).

Reidy, R. J. (2010). Eternal Egypt: Ancient rituals for the modern world. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

Remler, P. (2010). Egyptian mythology, A to Z [third edition]. New York, NY: Chelsea House.

Ruiz, A. (2001). The spirit of ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Algora Publishing.

Sauneron, S., & Lorton, D. (2000). The priests of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Shaw, I. (2003). Exploring ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Szpakowska, K. (2010). Religion in society: Pharaonic. In Lloyd, A. B. [Ed.], A companion to ancient Egypt, pp. 507–525. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Taylor, J. H. (2001). Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Taylor, J. H. (2010). Journey through the afterlife: The ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. London, UK: British Museum Press.

Teeter, E. (2011). Religion and ritual in ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Walton, J. (2006). Ancient Near Eastern thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the conceptual world of the Hebrew Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Publishing Group.

Winters, K. (2003). Voices of ancient Egypt. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.