The god named Set had already been worshiped in North Africa long before the Pharaohs came to power, during what is called the predynastic era. The first recorded appearance of His cult was in a southern Egyptian town called Nubt (“Gold Town”), which was named after its close proximity to a number of gold mines in the Eastern Desert. It later became known as Ombos to the Greeks and as Naqada to modern archaeologists. So great was this town’s accomplishments—which included metalworking, pottery, the emergence of writing, and one of the oldest pyramids in existence (Kjeilen, 2013)—that scholars refer to the final phase of predynastic Egyptian culture as “the Naqada Civilization” (Bierbrier, 2008). Since Nubt’s surviving artifacts have been dated from the Neolithic era (Kipfer, 2000), the predynastic worship of Set is known to have been one of the oldest religious practices in history, reaching back to the 4th millennium BCE at least (Rice, 2003).

The name Set itself was written in hieroglyphics as a mysterious animal with rectangular ears and a curved snout. It has multiple variants that are most basically rendered into English as sts, sth, s(w)th, s(w)t(y), st(y), and st (te Velde, 1977). Since the Egyptians wrote their words without vowels, it is impossible to be certain of how they originally pronounced this name. It was probably pronounced differently in different regions, with Sutekh being popular in the north and Set being popular in the south (te Velde, 1977). The Greeks and Copts pronounced it as Seth, which is the most easily recognized rendering today.

Plutarch (1970) thought that “the name ‘Set’ by which [the Egyptians] call Typhon denotes this: it means ‘the overmastering’ and ‘overpowering’ and it means in very many instances ‘turning back’ and again ‘overpassing.’” Variants of the name are clearly determinative to various Egyptian words for storms, violence, and upheaval (Betro, 1996). The animal in the hieroglyphic symbol has not yet been identified, but the Egyptians referred to it as the sha (Budge, 1934). Numerous authors have suggested that it might be a donkey, a giraffe, an aardvark, a wild canid of some variety, or even a fish (with the “ears” actually being fins), but there are reasonable objections to each of these theories (te Velde, 1977). Some scholars think the creature is either chimerical or extinct. In many cases, however, Set was also depicted in carvings and hieroglyphs as the other animals I have mentioned (Green, 2005). By the time of the Ptolemies and the Roman Emperors, He was most popularly drawn as a red-haired donkey or donkey-headed man (Plutarch, 1970; Webb, 1996).

Set is the soul of the force in nature that creates all storms. He rules the nighttime sky, the circumpolar constellations, and the desert wastelands that border Egypt (Webb, 1996). He was also regarded by His ancient worshipers as a heroic monster-slayer (Frankfurter, 1998), but not everyone shared this sentiment. This is because storms do not normally occur in Egypt, being more frequent in the desert regions. Even today, Egyptian crops are more than sufficiently fertilized by irrigation and the annual flooding of the Nile. Whenever storms do hit the Nile Valley, they are normally sandstorms that cause more harm to the crops than good (Zahran & Willis, 2009). So while the thunder gods of other cultures (e.g., Marduk, Thor, Yahweh, etc.) were usually associated with fertility, heroism and kingship, Set was more often viewed as a sterile alien interloper (te Velde, 1977). It is due to the red sands of the North African deserts that He is called “the Red Lord,” and all red-haired animals and people are considered to be His children (Remler, 2010).

It was not until after they became a truly agricultural society that most Egyptians began to view Set as a “problem.” This occurred after their country was united by its first Pharaoh, Menes, who was also given credit for constructing Egypt’s very first irrigation project (Woods & Woods, 2000). The ideas of kingship and agriculture were firmly correlated for this reason, and a god who opposed one was believed to oppose the other. Small wonder, then, that Set only remained popular among those who continued to live in the hostile desert regions. Such people required great fortitude to survive and were often gold miners, traders, outlaws, or political enemies who were sent to live in the wastelands as a punishment. Others, like the Tjemehu and Tjehenu tribes, continued to lead nomadic lives just as the predynastic Egyptians had done (Mertz, 2008).1

While those who followed the other Egyptian gods became members of an agricultural church-state (i.e., Egypt itself), Set’s followers were outsiders who remained apart from that order and who belonged to the world outside. This dichotomy is further explored in the story of Set’s rivalry with Horus. In this tale, the two gods once battled for control over human civilization. Set blinded Horus, and Horus amputated Set’s leg (or castrated Him in some versions). They were evenly matched blow-for-blow, however, and neither god could defeat the other. A peaceful resolution was later made by the god Thoth, who gave control over the Egyptian civilization to Horus. The hawk god then became incarnate in the messianic Pharaohs while Set was given power over “the wilderness,” which included everything outside the Pharaohs’ control (including the civilizations of other cultures). To sweeten Set’s end of the bargain—and to keep Him from challenging Horus again—He was also made the personal bodyguard of the sun god Ra, and He was given two concubines: the foreign goddesses Astarte (i.e., Ishtar) and Anath. Presumably, Set agreed to this arrangement and has been defending Ra and making merry with His exotic lady friends ever since (Lothian, 1997).

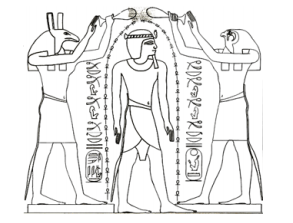

Unlike most other dualist myths in which a “civilized” god of light and a “barbarian” god of darkness come to blows, the story of Horus and Set ends with a divine peace treaty. Neither side is defeated or cast out, and their conflict is not resolved by war; both gods win and are appeased through divine legal counsel (Assman, 2003). One might expect the Pharaohs to have demonized Set as their Adversary, but the Red Lord never completely fell into disrepute until after the native government fell to foreign rule during the 4th century BCE. This means that despite His disturbing and frightening nature, Set continued to be a valid member of the Egyptian pantheon for roughly 2800 years after Menes united the country. During that time, each Pharaoh was thought to be personally coronated not only by Horus (who became incarnate within the priest-king during the process), but by Set as well. His place outside the Egyptian order made Him the perfect defender of “the temple of the whole world” against external threats. This was perhaps suggested by the formidable desert barriers that protected Egypt from invaders (Smith, 1998).

The reconciliation of Horus and Set is further illustrated by hieroglyphic drawings in which the two Divinities are conjoined to a single body (Budge, 1904). This image is essentially the ancient Egyptian equivalent to the Tao, for it represents the union of polar cosmic opposites into a synchronic unity. In this form, Horus and Set are both called “He with the Two Faces,” which indicates a belief that they are (and have always really been) two different sides of the same god (te Velde, 1977). In other texts, this mystical perspective is otherwise described as “the Secret of the Two Partners” (Mercatante, 1978). Horus and Set were even united in the office of the Pharaoh, who was considered to “be” Horus in his capacity as a ruler and to “be” Set in his capacity as a warrior (te Velde, 1977).

Most polytheistic traditions include a cosmogony or “divine family tree” that explains the ways in which their various gods are related to each other. The Egyptians, however, never had just one cosmogony; they had several. The question of which cosmogony a person accepted depended on her city of origin. The priests of her city were free to develop their own belief system based on the deity to whom they were assigned, which is how the Egyptians came to have several different Creation myths (Almond & Seddon, 2004). The three most well-known systems are those of Iunu (i.e., Heliopolis, the city of Ra), Khmun (i.e., Hermopolis, the city of Thoth) and Mennefer (i.e., Memphis, the city of Ptah). Since they existed in a polytheistic context, neither of these ideologies was thought to be exclusively “correct” (with the others being “incorrect”); they were merely different interpretations of the same cosmic phenomena and were thought to be simultaneously true (Naydler, 1996). It is possible that the priests of Nubt developed their own unique cosmogony, but there is no evidence to inform of us of what it might have been like. For this reason, most sources usually explain Set in terms of the Heliopolitan cosmogony.

This cosmogony begins with Ra’s emergence from the primeval waters of Nun, the primeval ocean. Ra then “ejaculates” Shu and Tefnut, the first male and female couple, into existence. Shu and Tefnut form an empty space in Nun and thereby define the limits of our cosmos. This leads to the births of Geb and Nut, who are the microcosm and the macrocosm. The physical structure they generate together creates a place in which life can exist (Allen, 2010). Geb and Nut then produce Osiris (i.e., fertility and regeneration), Isis (i.e., sexuality and birth), Set (i.e., aridity and storms), and Nephthys (i.e., barrenness and death). In what is perhaps the most difficult Egyptian concept to understand, the members of this divine family are simultaneously one with Ra and distinct from him. On the one hand, they are merely “limbs” that he uses to create and sustain the world; on the other, they each have their own personalities and can act independently of him (Naydler, 1996). This is why each Deity in the cosmogony was worshiped as “the Supreme Being” by his or her own followers (Almond & Seddon, 2004). At the same time, the entire world is Ra’s body, which is depicted as being a bubble of light on the surface of an infinite sea of darkness (Allen, 2010).

In this story, each generation of the gods is harmonious and dyadic—containing only one male and one female—until Set is born. His birth disturbs the normal process by causing the final phase of the sequence to contain two males and two females, as well as by introducing the aspects of nature that are hostile to life. This is further highlighted in the story of His traumatic birth, in which He literally explodes from the side of His mother, Nut. He was not born in the “natural” way or at the “natural” time; He impatiently tore Himself from Nut’s womb at a time of His own choosing (te Velde, 1977). It is perhaps no accident that Set is given as the seventh Deity to have emanated from Ra, with seven being the only single digit number that does not divide equally into 360 degrees (i.e., the total number of degrees in a circle). Furthermore, Set and Nephthys are the only couple in this scheme that cannot produce children and that eventually divorced. Nephthys produced the god Anubis through an illicit affair with Osiris (Najovits, 2003), and Osiris later produced Horus with Isis. Since he eventually became incarnate within the Pharaohs, Horus represents the point where the power of Ra is transferred from the gods to human beings (Baines, 1991).

According to Plutarch (1970), Nephthys was unhappy in her marriage with Set because of their inability to conceive. She so desperately wanted a child that she seduced Osiris, who is so fertile that he can even impregnate a barren goddess. Such is how Anubis came into being. When Set discovered what Nephthys had done, He drowned Osiris and dismembered him into fourteen pieces, burying thirteen of them throughout the world. He then fed the final piece of the body—Osiris’ phallus—to a fish. This event threw the rest of the pantheon into a panic, for Set had done something that had never been imagined before: He had actually killed another god. In time, Isis collected the remaining thirteen pieces of Osiris, reassembled them (with an artificial phallus), and restored the god to life. Then the two of them conceived Horus by magic and Osiris traveled to the Otherworld, where he now judges the dead and rules over the Field of Reeds. Meanwhile, Set terrorized Isis and her child until Horus came of age and sought to avenge his father’s murder. The war between Set and Horus raged on and on until they were peacefully reconciled by Thoth.

Aside from His sterility and His ability to kill other deities, Set is also separated from the other gods by His inability to die. Most of the gods are immortal in a cyclical sense, meaning that they ritually die and live again. Even Ra must continually regenerate himself, which he is said to do each day. This process is echoed in every cycle of nature, including the solar and lunar cycles and the turning of the seasons (Taylor, 2001). It is also why most of the gods were identified with phenomena that were perceived to “go” and “come back again,” including the Sun, the Moon, and the annual flooding of the Nile (Budge, 1934). Set, however, was linked to the Big Dipper in the constellation Ursa Major (Webb, 1996), which is circumpolar. It never “goes” or “comes back” from anywhere, but is always located in the same part of the northern sky (Schaaf, 1998). Likewise, there are no stories of Set ever dying or regenerating Himself; He is immortal in a much more linear sense of the term.

Set’s childlessness, deicidal power, and linear immortality all seem to be rooted in His “aberrant” sexuality, which first forced its way into the world through the so-called “reverse rape” of His mother. After all, it is only after His castration that Set finally assumes a more cooperative role in the pantheon as Ra’s bodyguard. Furthermore, the concepts of fertility and death have always been firmly linked. Why should a being reproduce if it will never pass away? Perhaps it is the ability to die that gives the other gods their power to procreate in the first place. In either case, Set’s castrated genitals are variously described as His “Thigh,” His “Bone,” His “Scimitar,” His “Iron-Tipped Spear” and “the Iron that Comes Forth from Set” (Budge, 1904; Budge, 1934; te Velde, 1977). This “Iron” is also the spirit double of the Big Dipper, and it is what Set uses to destroy chaos monsters and other enemies of Ra (just as Thor uses the hammer Mjollnir to slay giants in Norse mythology).

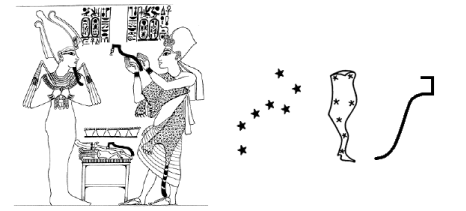

Set’s “Iron” was also represented as the was scepter, which is a staff with a forked base and the head of the sha beast at the top (Roth, 2011; Pinch, 2002). The Egyptian word was (pronounced “wahz”) means “dominion,” and the scepter was also called the “giver of winds” (te Velde, 1977). It is very clearly a phallic symbol, and it probably originated as a dried bull’s penis that was used to make a cane or walking stick. Since such objects are still made today in cultures that are totally remote from ancient Egypt—including the modern American hunter culture (Gordon & Schwabe, 2004)—this seems very likely. Set is also said to have taken the form of a bull when He was castrated (Simon, 2006). Clearly, His Iron is not a literal metal, but a kind of spiritual machismo. While Set still possesses this machismo, it is so powerfully destructive that it can only be allowed to exist as a thing apart from the god Himself.

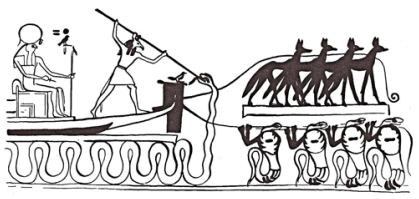

Contrasted against the gods is Apep,2 a gigantic “worm” or “serpent” that comes from outside the “bubble” of our universe. This creature is not a part of Ra’s body, but is completely alien to nature. Unlike most of the gods, it is not subject to death or rebirth under normal circumstances. It is also completely self-sufficient and requires no counterpart to exist. Paradoxically, Apep does not want to exist, but prefers the tranquil inertia of Nun; yet it cannot even destroy itself. This existential conundrum has driven the beast insane, making it devoid of any respect for nature, the gods, or mortals. It seeks instead to devour all of Ra and to prevent him from ever regenerating himself again. Should Apep succeed in doing this, everything—from the largest star to the smallest particle of dust—will cease to exist for all time (Asante & Mazama, 2009). And since the monster existed prior to Creation (as opposed to being created by the gods), it can never be completely vanquished or destroyed; it is more or less on equal footing with the gods (Caldecott, 2000).

The reason for reconciling Set with the rest of the gods now becomes abundantly clear. Since He is immortal in a continuous sense and has the power to kill other gods, Set is the perfect warrior to protect the world from Apep. He is able to keep the beast at bay precisely because He is the one aspect of Ra that came closest to becoming a monster. Now that He is reconciled with the rest of the pantheon, Set uses His Iron to smite Apep while the other gods are busy regenerating themselves (Gilmore, 2003). If this peace had never been achieved, the gods would have lost their last line of defense against the creature. And while Apep can never be completely destroyed, the Red Lord is literally the only thing that it fears. It is in His role as the Savior of Ra that Set was also identified with the planet Mercury (in addition to the Big Dipper), which was probably suggested by Mercury’s tendency to “travel” with the sun like a celestial bodyguard (Budge, 1934).

The battle between Set and Apep is a combat myth, or a tale in which a divine hero battles an ancient chaos monster. Other famous combat myths include the Babylonian Enuma Elish and the Christian Book of Revelation. In the former example, the god Marduk kills his mother, the dragon Tiamat, and creates the universe from her corpse. This battle takes place in the distant past, and it was re-enacted each year during the Babylonian New Year festival (Sproul, 1979). In the latter example, the archangel Michael casts Satan (who appears as a seven-headed dragon) down from heaven (Revelation 12:7–9, NIV); Christ then throws Antichrist and his False Prophet into hell (Revelation 19:19–21, NIV), and Satan is finally destroyed after 1,000 years of millennial peace on Earth (Revelation 20:7–10, NIV). All three of these battles are supposed to take place in the distant future, at the end of days.

There are many other combat myths, including the tales of Ba’al and Lotan (Green, 2003), Thor and Jormungand (Boult, 1940), Yahweh and Leviathan (Psalm 74, NIV), and Saint George and his dragon (Fontenrose, 1959). Yet the story of Set and Apep is probably the most unique. It is not limited to the distant past or future, and it does not happen only once. It is constantly repeated on a cyclical basis, occurring in the here-and-now as much as before. Furthermore, the hero is not the “darling” but the red-headed stepchild of His pantheon. Set is a sterile pansexual eunuch; He is not the typical “masculine” hero (á la John Wayne or Clint Eastwood), but more of a gender-bending “freak” (á la Alice Cooper or David Bowie). The fact that He is the Savior of Ra (and of the entire universe) is good news for anyone who has ever had trouble “fitting in” with their society, for it shows that even a total “misfit” can become a powerful force for good in the world.

Set is usually derided in most literature and media today as “the murderer of Osiris,” but His “crime” was really a blessing in disguise. It was Osiris’ raison d'être that he should be martyred and that new life should spring from his death. His sacrifice catalyzed his physical resurrection, the conception and birth of his son Horus, and the administration of justice in the great hereafter (with the just receiving eternal bliss and the wicked being damned). It is also by encountering the risen Osiris each night that Ra reboots his own regenerative cycle (Mojsov, 2005). None of these things would have been possible had Set never slain Osiris in the first place (Dumars, 2003). Perhaps this is why Set was also called “the Friend of the Dead” and was paradoxically said to have helped Osiris climb the Ladder of Heaven (Budge, 1971). There are many belief systems in which shamanic spirit journeys or initiatory magical workings are engaged by symbolic “dismemberments” and “deaths” (Pratt, 2007), and the “murder” of Osiris is best understood in this context (Webb, 1996).

One might describe Set and Osiris as resembling a cosmic gardener and a cosmic rosebush, respectively. If a gardener does not want his rosebush to go to seed, he must trim the bush of its aging flowers; this causes the plant to bloom again and again. In the same way, Set does not actually “kill” His brother, but merely prods him to exhibit his restorative powers. This is reflected in the Ceremony of the Opening of the Mouth, which involved pressing an iron adze upon the mouths of cult images that were to become vessels for gods or ghosts (Almond & Seddon, 2004; Glazov, 2001). This adze was shaped like the Big Dipper and was made of iron to serve as a magical “stand-in” for the Iron of Set (Simon, 2006). Essentially, Egyptian priests channeled Set’s destructive sexual power to transform lifeless images into living magical conduits. In this way, the same power that killed Osiris and that wards off Apep can also bring new life (te Velde, 1977). While Apep seeks to swallow the light of Creation forever, Set only “kills” that light to make it shine again.

Despite His unsavory reputation as a “murderer,” Set is said to eat only lettuce (te Velde, 1977), which is a strangely vegan choice for such a “barbarian” and “malevolent” god. If He were truly as “evil” as some people think, one would expect Him to eat far too much red meat. To further highlight this discrepancy, most of Set’s sacred animals—including the donkey, the okapi, the giraffe, the gazelle, and the oryx—are herbivores.3 Even hippos, as dangerous as they are, prefer the taste of grass to that of other animals.4 This suggests that vegetable matter was more often shared with the Red Lord as a religious offering, rather than flesh or blood. The only animals and people that were killed in relation to Set were killed to demonstrate hatred for Him, not worship. Red-haired donkeys, for example, were commonly pushed over cliffs to magically keep Set “away” during the Classical period (Plutarch, 1970). Red-haired people were also persecuted and sometimes killed for the same reason, which later informed the European superstition that redheads are somehow “aligned with the devil” (Spence, 1990).

In truth, Set’s demonization had little to do with Osiris, but was a response to several foreign occupations of Egypt. First came the Hyksos, a Semitic people who took control of the country in the 17th century BCE, and who worshiped Set as another form of their own god, Ba’al (Booth, 2005). Indigenous Egyptians thought that Set—who was supposed to protect Egypt from foreign threats—had allowed (or even helped) the Hyksos invade the country. These interlopers were eventually dethroned and were followed by the native Ramesside Pharaohs, who worked hard to restore Set’s reputation. Their efforts ultimately failed, however, when Egypt became occupied by the Persians circa 525 BCE, by the Greeks circa 332 BCE, and by the Romans circa 30 BCE. Foreigners (i.e., the Muslim Arabs, the Ottoman Turks, the French and the British) continued to dominate the country until 1953, when the Republic of Egypt was finally proclaimed (Humphrey, 2009). While Set was still worshiped by nomadic tribes well into the Roman period (Frankfurter, 1998), urban Egyptians used Him as a scapegoat for the end of their civilization (Assman, 2003).

At this time, Set was ironically (and perhaps deliberately) confused with Apep, which has caused some writers to mistakenly identify the monster as a “form” of Set (Budge, 1934; Spence, 1990). This dubious notion is what led the Greek historian Herodotus to link Set with Typhon, a monster that resembles Apep in Greek mythology (Gmirkin, 2006). For this reason, Set was most often called Seth-Typhon during the Greek and Roman occupations of Egypt (Webb, 1996). His followers became known as “Typhonians” and were accused of murdering people in their rituals. Actual Set worshipers were not the only targets of this blood libel, since Jews and red-haired people were also its victims (te Velde, 1977; Van Henten & Abusch, 1996). Worshiping Set—or being associated with Him in the public imagination for any reason—became a polytheistic prototype of what Christians would later call “Satanism.” The persecution of “Typhonians,” in fact, was a precursor to the various blood libels that would later be perpetuated against polytheists, Jews, homosexuals, women, redheads, “witches,” and “Satanists” throughout Europe, North America, and Australia (Cavendish, 1967; Fritscher, 1969; Medway, 2001).

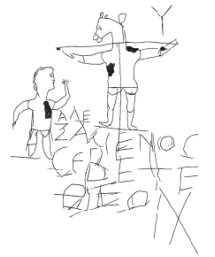

Ironically, the oldest image of Jesus Christ is an inscription on a wall in Rome called the Alexamenos graffito, which depicts Jesus as a crucified donkey-headed man (Viladesau, 2006). The donkey, of course, is a so-called “Typhonian” animal that is sacred to Set, and drawing someone with a donkey’s head was essentially the Roman way of depicting that person with “devil horns.” The author of the Alexamenos graffito was thereby intimating that Christians were really following Seth-Typhon (in the same way that Christians have always accused polytheists of worshiping Satan). This is because the early Christians were perceived by their contemporaries as a bizarre alien cult. They worshiped an executed criminal, they refused to acknowledge other divinities, and they perceived the world and the flesh to be fundamentally evil. As far as most people were concerned, Christians were mentally disturbed atheists whose very existence might incur the wrath of the gods. Who else but Set could be blamed for bringing such “undesirable” people into the world?

Further confusion resulted from the so-called “Sethian” Gnostics, who were a group of Jewish heretics that revered the biblical Seth (i.e., the third son of Adam and Eve) as their messiah (Pearson, 2007). Many authors have conflated this Seth with the Egyptian god (Carus, 1901), but there is no evidence that the two figures are related in any way (Fossum & Glazer, 1994). Their names, while superficially similar, are homonyms with completely different etymological origins (Klijn, 1977; Betro, 1999). Nevertheless, the superficial resemblance fueled a Greek and Roman belief that Seth-Typhon was the patriarch of the Jewish people (Budge, 1904). Such beliefs are reflected in several of the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri, wherein various names for the Jewish god (e.g., Iao, Sabaoth, etc.) are specifically used in invocations to Seth-Typhon (Webb, 1996). This was similar to how medieval Christian demonologists later used the names of Canaanite Deities (e.g., Ba’al) as names for demons, or even for Satan himself (Cavendish, 1967).

This is especially ironic since Coptic Christians—or the native Egyptians who were allegedly converted to Christianity by Saint Mark (Meinardus, 1999)—identified Set with Satan (Budge, 1934; Mercatante, 1978). In fact, it is from this identification that the Abrahamic devil acquired his red hair and forked tail (Gray, 2009). Even today, Set is more often compared to Lucifer than to any other mythological figure; some authors even claim that the Hebrew word Satan is etymologically derived from Set’s name (Ocansey, 2002; Flowers, 2012).5 For this reason, modern Set worshipers are easily confused with Satanists, and in more ways than one. The Red Lord’s more heroic role as the Savior of Ra—not to mention the theological necessity of His actions against Osiris—is often known only to studious Egyptologists and to modern practitioners of Egyptian polytheism.

1 It should hardly seem surprising that the Tjemehu were described as being blond or red-headed (Bunson, 2002), both of which were abnormal (i.e., “Setian”) hair colors to the Egyptians.

2 Many contemporary practitioners of Egyptian polytheism consider it wise to cross out

Apep’sname whenever it is written, so as to avoid attracting the monster’s attention (Wepwawet Wiki, 2011). I happen to share this belief, which is why the name is written in strikethrough text throughout this work.3 Except for the donkey, these herbivores are also artiodactyls or even-toed ungulates, meaning they are hoofed animals with an even number of toes (Eisenberg & Redford, 1999).

4 The only exceptions to this list are crocodiles, snakes and pigs (which are omnivorous).

5 I have yet to find any historical evidence for this claim whatsoever.

Allen, J. P. (2010). Middle Egyptian: An introduction to the language and culture of hieroglyphs. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Almond, J., & Seddon, K. (2004). Egyptian Paganism for beginners. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn.

Asante, M. K., & Mazama, A. (2009). Encyclopedia of African religion, volume 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Assmann, J. (2003). The mind of Egypt: History and meaning in the time of the Pharaohs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Baines, J. R. (1991). Society, morality, and religious practice. In B.E. Shafer (Ed.), Religion in ancient Egypt: Gods, myths and personal practice (pp. 99-123). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Betro, M. C. (1996). Hieroglyphics: The writings of ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Abbeville Press.

Bierbrier, M. L. (2008). Historical dictionary of ancient Egypt. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press.

Booth, C. (2005). The Hyksos period in Egypt. Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications.

Boult, K. F. (1940). Asgard and the Norse heroes. New York, NY: Biblo & Tannen Publishers.

Budge, E. A. W. (1904). The gods of the Egyptians, volume 2. New York, NY: Dover.

Budge, E. A. W. (1934). From fetish to god in ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Dover.

Budge, E. A. W. (1971). Egyptian magic. New York, NY: Dover.

Bunson, M. (2002). Encyclopedia of ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc.

Caldecott, M. (2000). Hatshepsut: Daughter of Amun. Bath, UK: Mushroom Publishing.

Carus, P. (1901). Anubis, Seth and Christ. Open Court, 15, 65–97.

Cavendish, R. (1967). The black arts. New York, NY: Penguin.

Dumars, D. (2003). The dark archetype: Exploring the shadow side of the divine. Franklin Lakes, NJ: New Page.

Ellis, R. (2004). Eden in Egypt. Chesire, UK: Edfu.

Flowers, S. E. (2012). Lords of the left-hand path: Forbidden practices and spiritual heresies. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Fontenrose, J. E. (1959). Python: A study of Delphic myth and its origins. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Fossum, J., & Glazer, B. (1994). Seth in the magical texts. Zeitschrift fur Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 100, 86—92.

Frankfurter, D. (1998). Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and resistance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fritscher, J. (1969). Popular witchcraft: Straight from the witch’s mouth. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Gilmore, D. D. (2003). Monsters: Evil beings, mythical beasts, and all manner of imaginary terrors. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Glazov, G. Y. (2001). The bridling of the tongue and the opening of the mouth in biblical prophecy. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press.

Gmirkin, R. E. (2006). Berrosus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic histories and the date of the Pentateuch. New York, NY: T & T Clark.

Gordon, A. H., & Schwabe, C. W. (2004). The quick and the dead: Biomedical theory in ancient Egypt. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Gray, C. (Director). (2009). Out of Egypt [Television series]. Silver Spring, MD: Discovery Channel.

Green, A. R. W. G. (2003). The storm-god in the ancient Near East. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Green, L. (2005). Seth. In Littleton, C. S. (Ed.), Gods, goddesses and mythology (pp. 1279–1284). Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Corporation.

Humphrey, A. (2009). National Geographic traveler: Egypt (3rd edition). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Books.

Kipfer, B. A. (2000). Encyclopedic dictionary of archaeology. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Kjeilen, T. (2013). Naqada. LookLex Encyclopedia website, April 25, 2013, http://looklex.com/e.o/naqada.htm (accessed April 25, 2013).

Klijn, A. F. J. (1977). Seth in Jewish, Christian and Gnostic literature. Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

Lothian, A. (1997). The mighty sons of Re. In The way to eternity: Egyptian myth and mankind. London: Duncan Baird Publishers.

Medway, G. (2001). Lure of the sinister: The unnatural history of Satanism. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Meinardus, O. F. A. (1999). Two thousand years of Coptic Christianity. New York, NY: The American University in Cairo Press.

Mercatante, A. S. (1978). Who’s who in Egyptian mythology? New York, NY: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc.

Mertz, B. (2008). Red land, black land: Daily life in ancient Egypt (2nd edition). New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Mojsov, B. (2005). Osiris: Death and afterlife of a god. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Najovits, S. (2003). Egypt, trunk of the tree: Vol. I: The contexts. New York, NY: Algora Publishing.

Naydler, J. (1996). Temple of the cosmos: The ancient Egyptian experience of the sacred. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International.

Ocansey, J. (2002). The roots of our faith: Ancient Egypt and the Bible. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, Inc.

Pearson, B. A. (2007). Ancient Gnosticism: Traditions and literature. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.

Pinch, G. (2002). Egyptian mythology: A guide to the gods, goddesses, and traditions of ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Plutarch (1970). De Iside de Osiride. Cardiff, Wales: University of Wales.

Pratt, C. (2007). An encyclopedia of shamanism, volume 1. New York, NY: Rosen Publishing Group.

Remler, P. (2010). Egyptian mythology, A to Z (3rd edition). New York, NY: Chelsea House.

Rice, M. (2003). Egypt’s making: The origins of ancient Egypt, 5000—2000 BC. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Roth, A. M. (2011). Objects, animals, humans, and hybrids: The evolution of early Egyptian representations of the divine. In Craig, D. (Ed.), Dawn of Egyptian art (pp. 194–202). New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Schaaf, F. (1998). 40 nights to knowing the sky: A night-by-night sky-watching primer. New York, NY: Henry Hold and Company, LLC.

Simon. (2006). The gates of the Necronomicon. New York, NY: Avon.

Smith, W. S. (1998). The art and architecture of ancient Egypt (3rd edition). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Spence, L. (1990) Ancient Egyptian myths and legends. Mineola, NY: Dover.

Sproul, B. C. (1979). Primal myths: Creation myths around the world. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Taylor, J. H. (2001). Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

te Velde, H. (1977). Seth, god of confusion: A study of His role in Egyptian mythology and religion. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

Van Henten, J. W., & Abusch, R. S. (1996). The depiction of the Jews as Typhonians and Josephus’ strategy of refutation in Contra Apionem. In Feldman, L. H., & Levison, J. R., Josephus’ Contra Apionem: Studies in its character and context with a Latin concordance to the portion missing in Greek (pp. 271-309). New York, NY: Brill.

Viladesau, R. (2006). The beauty of the cross: The passion of Christ in theology and the arts from the catacombs to the eve of the Renaissance. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Webb, D. (1996). The seven faces of darkness: Practical Typhonian magic. Smithsville, TX: Runa Raven.

Wepwawet Wiki. (2011).

Apep. Wepwawet Wiki website, December 10, 2011, http://www.wepwawet.org/wiki/index.php?title=Apep (accessed May 1, 2013).Woods, M., & Woods, M. B. (2000). Ancient agriculture: From foraging to farming. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publications Company.

Zahran, M. A., & Willis, A. A. J. (2009). The vegetation of Egypt. New York, NY: Springer.