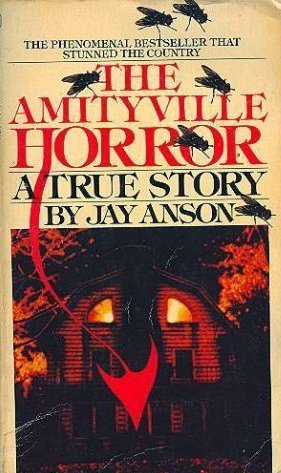

The Amityville Horror began as a hoax concocted by the late George Lutz, which he based on the real life case of Ronald DeFeo. DeFeo murdered his family one night at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, Long Island back in 1973, and the Lutz family were the first to move into that address afterwards. They only stayed there for one month, during which they claimed to be harassed by demonic voices, phantom pigs, invisible marching bands, and a mysterious black ooze dripping out of the walls. Neither of these stories has ever been substantiated, but Lutz landed a book deal with author Jay Anson, who novelized the story as The Amityville Horror (Prentice Hall, 1977). This was later adapted into a 1979 film starring James Brolin and Margot Kidder. For whatever reason, it became one of the most financially successful films of the 1970s, despite the fact that it was produced by American International Pictures (known best for their cheap drive-in schlock from the 1950s and 1960s), and the fact that it’s boring as shit.

Amityville was so successful, in fact, that it quickly spawned a prequel: Amityville II: The Possession (1982). This second film is ostensibly about the DeFeo family, but it takes so many sickening liberties with their lives that I can’t really endorse watching it. It takes its inspiration from Ronald DeFeo’s murder defense, wherein his lawyer, William Weber, seriously tried to push the claim of “demonic possession” in court. This seems especially tasteless considering that George Lutz and William Weber turned out to be in cahoots with each other at the time. (Not for long, though; Lutz soon tried to sue Weber, as well as several other people, for saying things about him he didn’t like. This guy seems to have spent more time suing people than he ever did working an honest job.) Yet Amityville II was also successful at the box office, which meant another film would soon be following in its wake. So in 1983, Orion Pictures gave us Amityville 3D, which is commonly thought to be even worse than the original Amityville.

The thing is, I actually enjoy Amityville 3D quite a bit; in fact, I think it’s the best Amityville film ever made. (Don’t get overly excited now—that isn’t really saying much!) One thing I like about this one is the fact that it isn’t “based on a true story”; it’s completely fictional, and it never claims to be otherwise. Sure, the story is abysmally stupid, and the characters are more two-dimensional than you can possibly imagine. I can’t even remember any of their names; I just remember Tony Roberts plays an asshole skeptic who moves into 112 Ocean Avenue and stubbornly refuses to believe it’s haunted. Never mind the fact that it kills his best friend (Candy Clark) and his daughter (Lori Loughlin). Then he and his ex-wife Tess Harper get help from Dr. Robert Joy to free their daughter’s soul from the house. There’s also a slimy Bug-Eyed Monster living in the basement, and it seems to be responsible for all the weird shit that happens in the house. That’s pretty much the entire plot right there; there’s nothing about the DeFeos or the Lutzes, and nobody connected with the Amityville Horror hoax appears to have collected any royalties from this entry (which automatically makes it better than either of its predecessors, as far as I’m concerned).

Mind you, Amityville 3D is not what I would call a “good” movie by any means. It’s just that it chooses to exploit a silly movie theater gimmick (3D camera photography) instead of a real-life murder case, which I find much more forgivable. Yet there are some things about this film that I truly enjoy. For one thing, it scared me pretty badly when I first saw it as a kid. In a sequence that shamelessly rips off The Omen (1976), Candy Clark’s character discovers a demonic face in the photos she has taken of the 112 Ocean Avenue property. She freaks out and goes to warn Tony Roberts, but then gets harassed by a demon fly while she’s driving in her car. She crashes her vehicle and is then set on fire, and as she dies, she screams one of the most convincing screams of pain I’ve ever heard in any horror flick. Now up until this point in the film, Clark is built up as being the main female lead, so it was really unexpected (not to mention upsetting) to see her get bumped off like that. It’s not an easy scene for me to watch even as an adult, so I have to give the creative team behind Amityville 3D a great deal of credit for scaring me pretty good.

Robert Joy’s character is a parapsychologist who works at some nameless university or institute somewhere, and who is both a “believer” and a “skeptic” at once. He clearly believes in the paranormal, but he’s slow to accept any particular claims about it without sufficient evidence. He was likely only written into the film to make it feel more like 1982’s Poltergeist (which features a number of similar characters), but I enjoy his presence all the same. The other characters are either too quick to believe whatever wild-eyed crap they hear (like Candy Clark and Tess Harper), too quick to dismiss it (like Tony Roberts), or too quick to fuck around with it (like Lori Loughlin and her teenage friends). Of course, the believers turn out to be right about everything in the end; but Robert Joy seems to be the only person in Amityville with a good head between his shoulders, and he’s charming and likable to boot.

It’s too easy to pick this film apart for everything it does wrong; my only serious complaint against it is that there just isn’t enough of the gooey booger monster that shows up at the end. It would have been much more impressive if the writers had decided to unleash this beastie at the beginning of the final act, so he can raise some serious hell for the last 20 minutes or so. As it is, we only see the damn thing for a few seconds before it scorches off Robert Joy’s face and drags his ass down to hell. Then we get some telekinetic-fu as Tony Roberts, Tess Harper, and the rest of Robert Joy’s investigative team get thrown around by invisible forces throughout the house. This part is actually pretty entertaining (especially the shot where the basement door explodes and crashes into one of the scientists, resembling a live-action Looney Tunes segment); but I really wanted to see some monster-fu instead. Oh well, at least the house blows up; if I can’t have my fill of slimy glopola goodness, I’ll settle for a nice random explosion!

In the earlier movies, the evil of the house is “confronted” by the Roman Catholic Church. The first movie features Rod Steiger as a priest who tries to help the Lutzes from afar, but who really doesn’t accomplish anything useful in the end; he just sort of loses his marbles, and then the movie forgets about him. The second film features a priest who tries to perform an exorcism on the Ronald DeFeo character, but he only succeeds in getting himself possessed instead. In Amityville 3D, Robert Joy’s character is a little more successful in dealing with the evil. (I mean, he does piss it off enough to make it blow its own home to smithereens; that’s got to count for something, right?) This transition from relying on organized religion to relying on quacky pseudoscience for answers was characteristic of the early 1980s. This was the era when the New Age movement really let fly and when “ancient astronauts” were all the rage. Not that I’m criticizing anyone for believing in that stuff if that is what they wish to believe; I just think it’s fascinating that the Amityville filmmakers would choose to take this course. The entire point of 1979’s The Amityville Horror was to cash in on earlier films like The Exorcist (1973), which is practically a late night infomercial for the Catholic Church. Amityville 3D is more like the bastard stepchild of Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape (1972), which uses scientific speculation to explain its supernatural events.

If it seems I am being too hard on the Lutzes and their fellow conspirators, it’s because their little hoax was just one of several that fed into the Satanic Panic of the 1980s. Of all the paranormal investigators who ever looked into their story, Ed and Lorraine Warren are perhaps the most famous and well-known. You might remember their names from all those Conjuring and Annabelle movies that have been produced over the past decade. Ed and Lorraine were a self-styled demonologist and clairvoyant, respectively, who claimed to have investigated over 10,000 hauntings together between 1952 and 2006. And during the late 1970s and 1980s, they were featured on damn near every TV special about the paranormal you might care to mention. My first exposure to them was in Scream Greats Volume 2: Satanism and Witchcraft, a direct-to-video “documentary” from 1986, wherein the Warrens insisted that organized “satanic ritual abuse” (SRA) is absolutely real. These hucksters made their fortunes by hoodwinking people into thinking that minority faiths like mine want to abuse and butcher your children, and the Amityville hoax is what facilitated their rise to fame. Granted, the Warrens weren’t the only SRA-peddlers in business at the time, and they certainly weren’t the worst. But whenever I see a trailer for yet another “Conjuring Universe” movie that probably cost about $140 million to produce, it just makes me feel a little queasy, you know?

There are several other Amityville films that came out after Amityville 3D, but only one of them—the 2005 remake starring Ryan Reynolds—was ever released theatrically. The rest are all direct-to-video or made-for-TV cheapies. The ones that were produced by Steve White—Amityville: The Evil Escapes (1989), Amityville: It’s About Time (1992), Amityville: A New Generation (1993), and Amityville: Dollhouse (1996)—are actually pretty enjoyable in my opinion; but they have almost nothing to do with Amityville or the house at 112 Ocean Avenue at all, so their titles are misleading at best.