Prior to the 1950s, creature features were dominated by gothic characters like vampires, werewolves, and Frankenstein’s monster. This all changed after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At the height of the Cold War, Count Dracula and the Wolf Man just didn’t seem that frightening anymore. Now people were worried about the effects of atomic radiation. Would it cause terrible mutations to plague the earth (like in 1954’s Them)? Would it awaken prehistoric monsters and drive them to seek revenge (like in 1953’s The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms)? Would it attract the attention of aliens who could easily conquer or even destroy us (like in 1951’s The Thing From Another World)? This was the age of the “atomic horrors,” when people wrestled with the dark side of science. In many of these films, the horrific events result from unethical scientists who overstep the boundaries between mortals and the gods. By upsetting the cosmic balance in this way, these anti-heroes enable the Chaos Serpent to wreak havoc upon the earth in any number of forms. They are, in fact, the direct progeny of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, who had a much easier time adapting to the atomic era than either of his more supernatural colleagues.

The tropes of the “mad science” subgenre came into much clearer focus during the aftermath of World War II. It was absolutely horrible that the United States dropped not one but two atomic bombs on Japan during the war. But lest we forget, the Japanese committed some truly ghoulish atrocities as well. Kamikaze suicide flights; the attacks on Pearl Harbor, Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong; the systematic extermination of 30 million Filipinos, Malays, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Indonesians, and Burmese; the Nanking, Manila, and Kalagong massacres of civilians; the use of chemical weapons, biological warfare, and human experimentation on civilians and prisoners of war; the list goes on and on. The atrocities of Imperial Japan rival those of Nazi Germany, and for better or worse, the A-Bomb was the only thing that stopped them. And though Japan and the United States have been peaceful allies ever since, Japan continues to be haunted by the experience of being bombed with nuclear weapons.

When the U.S. started testing hydrogen bombs on the Marshall Islands during the 1950s, a Japanese fishing boat called The Lucky Dragon 5 was accidentally exposed to fallout from one of the exploded bombs. The entire crew was contaminated and suffered nausea, headaches, and bleeding gums. The chief radio operator, Aikichi Kuboyama, died in terrible agony and pain, praying that he would be the last victim of such terrible weaponry. Next thing anyone knew, the whole country of Japan was plunged into a panic, and that’s when the guys at Toho Studios decided to make a film about nuclear chaos as a living thing. Pulling together the creative team of director Ishiro Honda and special effects wizard Eiji Tsuburaya, it wasn’t long before Japanese movie screens were showcasing everyone’s favorite Iguanadon/Stegosaurus/Tyrannosaurus hybrid, the one and only Godzilla (or, as he is known in Japan, Gojira).

The original Godzilla, released in 1954, begins with a re-creation of the Lucky Dragon 5 incident, wherein the crew of a Japanese fishing boat notice that the ocean is glowing around them. Something roars from beneath the surface of the water, and the boat burns and sinks. A few of the men survive, but by the time the Japanese coast guard rescues them, the survivors are all suffering from radiation sickness. Not long after that, a fishing village on Odo Island is destroyed during a storm. A scientist named Kyohei Yamane (played by Takashi Shimura) leads a detailed investigation of the island, only to learn that it’s experiencing nuclear fallout. All the wells are poisoned, and the place is riddled with giant radioactive footprints. Then Godzilla shows up, and everyone gets a real good look at him. Lucky for them, Big G is just going for a walk, not seeking to cause any trouble, and he soon returns to the sea. Dr. Yamane and his team then return to Japan and report what they’ve found to the government, which promptly divides itself between those who think the story should be kept under wraps (and who are mostly men) and those who think they should be warning everybody in the country about what’s really happening (and who are mostly women).

Now Dr. Yamane has a lovely daughter named Emiko (played by Momoko Kochi), and she is caught in a tragic love triangle. She’s engaged to marry a scientist named Dr. Daisuke Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), who is a World War II veteran. He was injured in the war, now wears an eyepatch, and seems to be alienated from everyone else around him. Unfortunately for Dr. Serizawa, Emiko has fallen in love with another dude named Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada), a salvage ship captain who’s involved in the investigation of Godzilla. But before Emiko can break off their engagement, Serizawa shows her why he’s become so alienated from everybody. He takes her to the basement of his house and shows her a new invention he’s been working on. We can’t really see what the device does just yet, but whatever it is, it makes Emiko scream and faint. And when she leaves Serizawa’s house, it’s like she’s been lobotomized.

Meanwhile, the government begs Dr. Yamane for a way to kill Godzilla; but as Yamane himself points out, the creature has absorbed all that fallout from those H-Bomb tests at the Marshall Islands. In other words, Godzilla literally eats, pisses, and shits pure atomic energy; so just how the fuck is anyone supposed to kill the big guy? Furthermore, Dr. Yamane does not want Godzilla to die, but thinks the creature should be contained and studied instead. He figures there are probably all kinds of things scientists can learn from an animal that’s strong enough to survive a atomic blast. But the government doesn’t listen; it just tries to neutralize Godzilla before he becomes too much of a nuisance. This only pisses the monster off, of course, and Big G eventually hits the city of Tokyo for a night on the town.

When Godzilla attacks Tokyo for the first time, there’s absolutely nothing humorous or “cheesy” about it. We see men being set on fire and screaming for the mercy of death. We see a mother holding her children and crying, “We’ll be with your Daddy in heaven very soon, now!” We see news anchors offering their lives to keep reporting on Godzilla for any listeners who are still trying to escape the city. We see hospital doctors waving Geiger counters over newly orphaned children (while the kids scream for their dead parents), and we see schoolchildren singing prayers for all the people who’ve died. These scenes are made even more disturbing by the fact that they weren’t just “dreamed up” by a storyboard artist. They’re based on real events Ishiro Hondo personally witnessed during the aftermaths of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. So in a way, the 1954 Godzilla isn’t just a science fiction/horror film; it’s practically a documentary.

Some have argued that Godzilla is a work of anti-American propaganda; surely, having the giant lizard puke radioactive shit all over Tokyo is really America’s fault, right? But it seems to me that Big G is actually a self-critical symbol of Japanese ultraviolence turned against itself. The way Ishiro Honda frames the narrative, it feels almost as if he thought Japan deserved to be wiped off the face of the planet by an atomic fire-breathing dinosaur. Godzilla is like a judgment from the gods, sent to humble Japan for every horrific war crime it ever committed as an Axis Power. And as the film eventually reveals, the only way to defeat the monster is by creating something even worse than what awakened him. That’s when Emiko finally reveals what Dr. Serizawa’s been hiding in his basement all this time.

Serizawa fought on the wrong side of an immoral war. He has directly experienced true evil more than any other character in the entire film. Perhaps he has even committed a few wartime atrocities of his own. Horrified by what probably he saw (and did) during the war, he is now a devout pacifist; yet he has invented something called “the Oxygen Destroyer,” completely by accident. This device somehow removes all oxygen from the body, instantly skeletonizing its victims; and after witnessing the holocaust in Tokyo, Emiko and Ogata try to convince Serizawa to use this new weapon against the beast. But Serizawa refuses; he’s terrified that if his Oxygen Destroyer is ever discovered, corrupt political forces from around the world will conspire to use it as a new weapon of war. What if they somehow coerce or trick him into creating more of these hellish devices? And if nuclear weapons have given us Godzilla, what terrible thing will the Oxygen Destroyer bring in its wake? That’s when Ogata says the most chilling line in the entire movie. He admits that Serizawa’s fear might become a reality; then he points out that Godzilla is reality.

Serizawa agrees to use the Oxygen Destroyer, but he destroys all of his research first to prevent anyone from ever building another one. Then he is joined by Emiko, Ogata, Yamane, and the entire Japanese navy out at sea. They find where Godzilla is currently located, and Ogata and Serizawa descend together to the ocean floor. There they find Godzilla resting, at peace with himself and his surroundings. This is the most disturbing part of the film for me personally, because it reminds us that Godzilla is just an animal, another innocent victim of World War II. After Ogata returns to the surface, Serizawa activates the Oxygen Destroyer; then he decides to stay with Godzilla. He gives his life to take the secret of his invention to his grave, and I sense he also thinks it would be unjust for Godzilla to die alone. When Godzilla and Serizawa are skeletonized together, it never fails to make me weep profusely. Godzilla is like Set in His role as the slayer of Osiris; he’s this frightening destructive force that’s been pushed too far, and which has finally gone berserk. But Serizawa is like Set as the Champion of Ra; he is capable of causing great destruction, yet he’s a good guy who wants to protect civilization from chaos. In dying together (during their first and only meeting), these two versions of Set come together as one. Normally in this kind of movie, it’s a “good” thing when someone figures out a way to defeat the monster; but here, the creature’s death is treated as a tragedy and a potential starting point for even more violence and horror to come.

Ishiro Honda's Godzilla was so tremendously successful in Japan that an American film company called Jewell Enterprises bought the international rights for the movie in 1956. Then they adapted the film for an English-speaking audience, and this went far beyond just dubbing the film with American voice actors. Due to the sizable rift between the American and Japanese styles of storytelling, Jewell totally restructured Godzilla to make it more accessible to the average American moviegoer. They filmed entirely new scenes with Raymond Burr, who played a new character named Steve Martin (not to be confused with the comedian). This character was then edited into the film (along with some Japanese-American actor doubles), and he was made a news reporter so he would have an excellent excuse for asking so many questions of the Japanese characters. This would give American audiences a character with whom they could identify, and to whom important plot elements could be explained.

Truth be told, most Americans would never have seen Godzilla if Jewell Enterprises hadn’t re-tooled the film for its own purposes in this way. In 1956, World War II was still fresh on everyone’s minds, and Americans were still racist as fuck against Japanese people. While the original Toho film isn’t “anti-American” at all, the folks at Jewell worried that some viewers might interpret it that way. They wanted the audience to identify with the Japanese characters as much as possible, not react to them with hostility. Plus, adding Raymond Burr to the mix does absolutely nothing to brighten or cheapen the sequence in which Godzilla destroys Tokyo; the entire segment is still just as dark and depressing as it is in the Japanese cut. If it hadn’t been for Jewell’s re-packaging of the film, no one outside Japan would even know about Godzilla today. It’s definitely not above criticism, and it’s certainly inferior to the original Japanese cut; but Jewell’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters (the American title) still deserves some respect for what it’s given us. (Besides, you’re missing out on the full Godzilla experience if you only watch one version of the film or the other.)

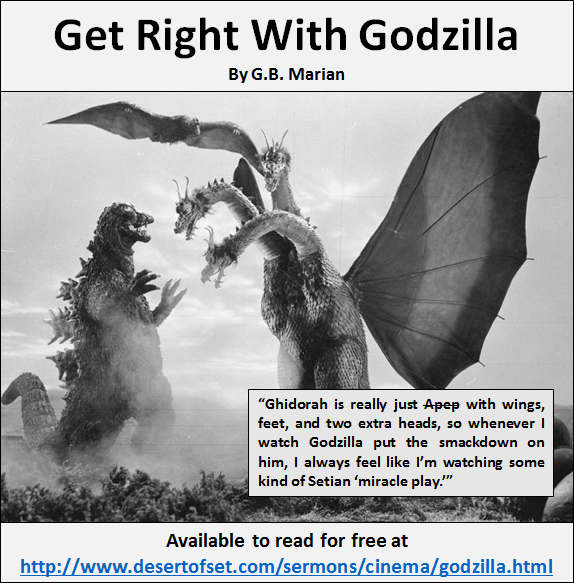

At the end of Godzilla, Dr. Yamane predicts that if people don’t end the nuclear arms race, another Godzilla might eventually appear to punish the world again. He was proven correct less than a year later when the much less impressive Godzilla Raids Again was released in 1955. Since then, Godzilla has appeared in over 30 different films. One of my personal favorites is Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster (1964), which is when Godzilla becomes a defender of the earth rather than its potential destroyer. A three-headed space dragon named King Ghidorah shows up and starts burning everything to the ground with his yellow lightning breath. Then Mothra, a giant caterpillar goddess, appears and tries to get Godzilla and Rodan (a giant pterosaur) to help her kick Ghidorah’s ass. This leads to one of the most endearing scenes in any Godzilla film ever, where the three beasties actually speak to each other (while being translated for the human audience by Mothra’s twin fairies). Godzilla and Rodan say they don’t give a shit what happens to humankind; they just want to be left alone. So Mothra goes to face Ghidorah herself, only to have her ass handed to her; and when Godzilla and Rodan see that, they get royally pissed and start beating Ghidorah like he owes them money. It’s one of the greatest monster throwdowns ever made!

This sequence is so damn important and inspirational to me, I’m going to throw up a video review someone else has made about it, just so you can see some clips.

Godzilla’s evolution from apocalyptic monster to child-friendly superhero is a fascinating discussion in and of itself. Recall that in the original 1954 film, Big G is a lot like Set as the slayer of Osiris. The story goes that once His rivalry with Osiris was resolved, Set was “reigned in” by the rest of the gods to save them from Apep, the Chaos Serpent. In much the same way, Godzilla starts out in the first movie as an innocent freak of nature who goes apeshit and almost nukes the entire planet; then, in Ghidorah, the world realizes it needs Godzilla to defend us from even worse monsters that just want to eat our planet. Ghidorah is really just Apep with wings, feet, and two extra heads, so whenever I watch Godzilla put the smackdown on him, I always feel like I’m watching some kind of Setian “miracle play” (with Godzilla and Rodan as a combative Set and Horus, respectively, and with Mothra as Thoth the mediator).

Since Godzilla’s rise to fame, Hollywood has tried adapting him for American audiences a number of times. In 1998, Dean Devlin and Roland Emmerich produced that terrible remake starring Matthew Broderick. It’s odd that they even chose to name the film Godzilla, considering that it’s actually a remake (or perhaps a parody) of The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953). Any hardboiled Godzilla fan will tell you the 1998 film stinks and should be ignored at all costs; but in 2014, director Gareth Edwards tried adapting Big G for the West once again. And while audience reactions have been very mixed, I was quite pleased with the result myself. It is surprisingly not a remake of the 1954 original, but more of an homage to all the sequels that make Godzilla the hero. Michael Dougherty’s 2019 follow-up, Godzilla: King of the Monsters (named after the Raymond Burr re-edit from 1956), was even better in my opinion, since it’s more or less a remake of Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster (complete with Mothra and Rodan teaming up with Godzilla). There’s even a scene that pays homage to the Oxygen Destroyer sequence from 1954, and it makes me cry like a baby whenever I see it. These newer Godzilla flicks might not be to everyone’s liking, but I wholeheartedly approve, and I can’t wait to see more of them.