Each religion has its concept of the Underworld; but what is this dark and mysterious plane, exactly? In popular culture, it’s usually pictured as a dark, nightmarish world that exists underground, and which is filled with tormented ghosts and demons. In fact, this notion of the Underworld seems to have influenced the Christian idea of hell, except that only “bad” (i.e., non-Christian) people are thought to go there. In ancient Paganism, however, almost everyone was thought to go to the Underworld, save for heroic warriors and kings (who reigned with the gods in heavenly places like Valhalla). Going there had nothing to do with whether you were good or evil in life; it was basically a matter of social status. Important people were noticed by the gods and welcomed into their various heavens, while common working class folk were expected to eat mud, drink tears, and gnash their teeth down there in the darkness forever.

Or were they?

The ancients might not have been so rigid in their beliefs as the experts might think. Our information about this stuff is based on writings from the tombs of important kings and nobles. Common people usually didn’t know how to read or write, so there is very little for us to go on when it comes to assessing their opinions on eschatology. It’s only natural that kings and chieftains would think they’d get a better place in the afterlife than their subjects; but does this really mean the common people couldn’t expect to enjoy a happy afterlife at all? In many cultures, regular people would bury their ancestors beneath the floorboards of their homes. They would keep altars for these relatives and make votive offerings to them on a frequent basis. The deceased were even buried in a fetal position, with their faces turned to the West (the direction of the setting sun). This indicates a belief that even common people could expect a rebirth in the next world, despite the fact that they weren’t all-important monarchs with massive reputations or egos.

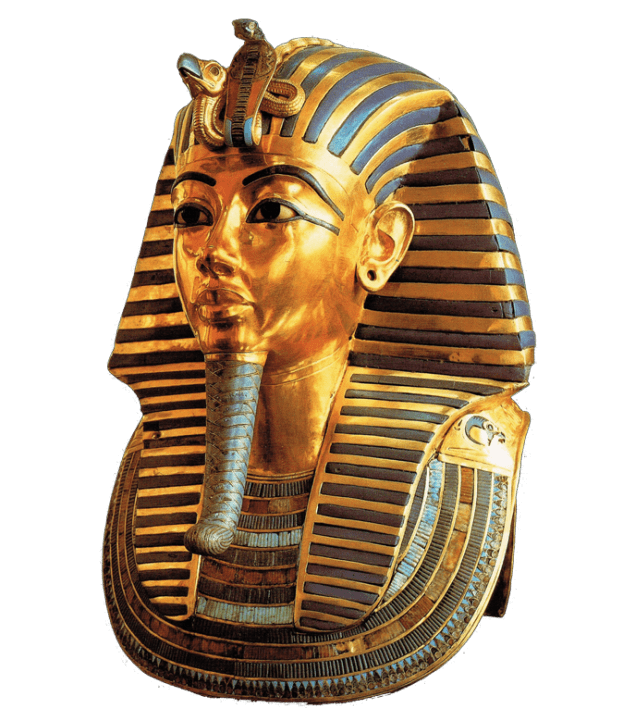

The evidence available to us shows that the Egyptian version of the Underworld was much more favorable to the common person than many others. The Egyptians called it Duat, which means “Place Where the Sun is Born” according to Maria Betro’s Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt (1996, Abbeville Press). Now why do you suppose they would refer to the Land of the Dead by such an optimistic-sounding name? Because it is where Ra, the Creator of the universe, crosses paths with Osiris each night to be reborn. As the sun god, Ra “dies” whenever they cross beneath the horizon, thereby passing into the realm of the invisible. While they are there, Ra has to be regenerated by Osiris, who was the first of the gods to die and rise again. Once this nocturnal meeting in Duat occurs, Ra begins to be reborn, a process that culminates at the break of dawn. So from the Egyptian perspective, the Underworld isn’t a place of death or decay, but of new energy and life. Duat is not just a destination for the past, but also a source of the yet-to-be.

There are some Kemetic reconstructionists who feel that Set’s role in the Osirian drama should never be celebrated; but prior to Osiris’ death, none of the gods knew what death was even like. Mortals would live and pass away upon the face of this earth, but did the gods care? Highly unlikely. It wasn’t until Set proved that they too can die (and that He can make it happen) that they started empathizing with our human fear of death. And just as Osiris spent his life traveling throughout the world, teaching people to plant crops, establish government, and stop eating each other like cannibals, so too would he implement similar reforms in Duat. Instead of just leaving everyone to wail and moan in darkness for all time, Osiris made it so the good-hearted will go to paradise and the evil-hearted will be destroyed (regardless of anyone’s station in life while they were still alive). If Set had never slain Osiris in the first place, none of this would ever have happened; so it is that good things sometimes need bad things to make them happen.

With Osiris, it is your heart that determines your afterlife, not your power or riches. Even loyalty to the god himself is not a factor, given that the “42 Negative Confessions” make no reference to accepting any particular doctrines or dogmas. The Egyptians expected to be judged for things like murder, rape, and stealing food that’s been offered to the gods, not for their theological opinions or beliefs. You don’t even have to worship Osiris to be welcomed into his Field of Reeds.

There is some confusion as to “where” Duat is, exactly. We used to think the Egyptians perceived it as being literally underground; but more recent discoveries show that the physical world and Duat were viewed as being two sides of the same coin. The universe is like a giant body, and the world of matter (including everything in outer space) is just the visible outer skin of that body, while Duat is the invisible flesh and bone beneath that skin. The hieroglyphic for Duat resembles a five-pointed asterisk in a circle. The asterisk itself is the hieroglyphic for seba or “star,” and the circle represents rebirth. The star is also “hidden” within the circle, so as to become “invisible.” But doesn’t this image also make you think of something else in particular? I think it looks like it could be a possible origin for the pentagram.

Duat is not just one place, but a continuum filled with myriad worlds. Osiris has the Field of Reeds, an agrarian paradise filled with eternal booze and lovemaking, while Ra has the Solar Barque, which resembles a phosphorescent cruise ship. Hathor has a Sycamore Tree where she offers refreshments to the deceased, and Set of course has His Secret Place “behind” the Big Dipper. But before any soul can proceed to either of these various realms, it must undergo a procedure called the Weighing of the Heart, wherein its collective deeds (symbolized as their “heart”) are measured against the whole of Ma’at (the cosmic balance, symbolized as an ostrich feather). If the heart is heavier than the feather, the soul is fed to the daemon Ammut, whereupon it ceases to exist for all time. If this happens, the spirit of the deceased—which is separate from their soul—is left to linger on this earth as a ghost (or even a qlipha). But if the soul is more or less in good standing with Ma’at, it is re-united with its spirit and transfigured to become an akh (“shining one”). Then the departed is free to roam any place in Duat the gods might permit them to visit.

There are certain places where the barrier between us and Duat seems especially thin. Cemeteries and tombs are the most immediate examples, but I would also cite hospital maternity wards, where new lives are constantly being born. (Remember, Duat is the Land of the Yet-To-Be as much as it is the Land of What-Used-To-Be.) There are also certain times when Duat becomes more accessible, but these are not identical across the globe. For example, the veil grows thinnest in Egypt during holidays like the Wag Festival, which traditionally occurs sometime in August or September; but here in North America, the veil is thinnest at Hallowtide. Then again, if you live in the southern hemisphere, the cross-quarter days will fall on different dates due to the seasons being reversed. So the point of transition between our surface reality and Duat can vary based on your geographical location and the time of year.