A rambling discussion on horror movies and spirituality with two of my brethren in the LV-426 Tradition!

I am proud to announce that for our next two adventures, I will be joined by two of my brethren from theLV-426 Tradition, Tony and Patrick. Together we will discuss some of our favorite horror movies, and what they mean to us spiritually!

Tony and I met in Texas in 2000, and when we started meeting for Sabbats back in 2003, the LV-426 Tradition was born. Tony was also the frontman for an awesome death metal band called Hexlust, which released the album Manifesto Hexcellente in 2015.

Patrick and I met in Michigan in 2009, and he joined the LV-426 Tradition in 2010. Patrick is a writer, podcaster, and lover of all things play. He also writes for Fyx, a blog about video games.

Tony and Patrick are not just my friends, but my brothers in Set. We treat each other like family, and we are truly blessed to know each other. These gentlemen are also two of the most brilliant and analytical Setians I have ever had the pleasure of meeting. So without any further ado, please welcome Tony and Patrick to the show!

G.B.: Welcome brothers! Thank you so much for joining me today, just in time for Halloween, the Season of the Witch, to discuss two of my favorite things with me: our spiritual orientations and our favorite horror movies, something that many people probably don’t think would be readily connected. But as we know in our circle, a monster romp can often be much more divine, thought-provoking, and life-changing than any Kirk Cameron movie!

Tony: Well, he did save Christmas, even though it didn’t need to be saved in the first place! [Laughter.]

G.B.: Horror movies have definitely been a part of my life ever since I can remember, from being a little kid. I think probably the earliest movie I ever saw was the old universal Boris Karloff Mummy movie from 1932, where he plays Imhotep, who I learned was actually a real person in ancient history, not just a meet-up monster villain. The actual Imhotep was nothing like the Boris Karloff monster. He was like a fucking doctor or physician, and he was one of the first people in history to develop medical treatments for people that were completely scientific and not magical. His methods didn’t have anything to do with repelling spirits or anything like that; it’s more like, “No, this is something to do with some kind of disease.” And he also constructed the Djoser Pyramid, so seeing The Mummy was kind of a big deal for me. There’s just something about killer mummies that I love, but it was also very educational because it opened the door for me to learn about Imhotep.

G.B.: And then of course, I think everybody who stands within 20 to 30 feet of me probably knows the Halloween movies are fucking religion to me. I always make a big deal every year, on October 31st, about actually celebrating the holiday as a time for remembering our sacred ancestors, the Blessed Dead; they might not necessarily be relatives, but it can be observed for anyone who has passed away and whom we miss.

G.B.: So Tony, what have been some of your favorite monster romps that make you think about spiritual shit?

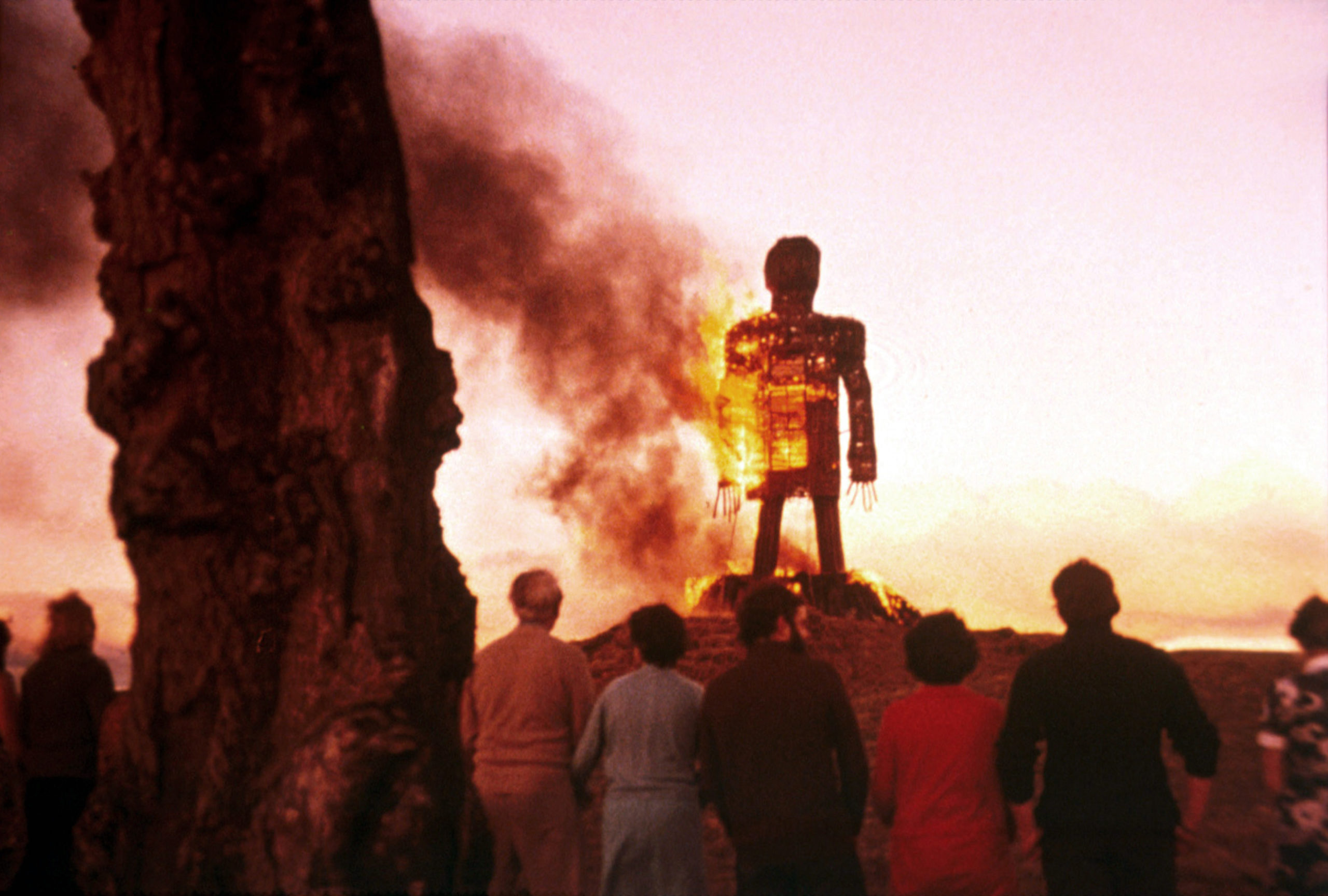

Tony: Many horror movies I see, the older I get, the more I review them, the more I see them; unfortunately, the same tale is told over and over again, and it’s a very straight, narrow Christian viewpoint of temptation, lust, punishment, and redemption. This same theme is used over and over and over again, whether it’s added with blood, added with sex, etc. That’s why I really enjoy The Wicker Man (1973). If that movie was remade yet again today, they would really play up on the fact that everybody’s having copious amounts of sex without being observant of the monogamous lifestyle. Or the fact that they’re “taking the Lord’s name in vain,” but in their Pagan God viewpoint. But in the 1970s film, you don’t feel like the people on that island are bad people. It’s just “Hey, we got a job to do, and we have a set of rules that we follow. We have a set of beliefs and creeds that we follow, and you’re coming in here and trying to destroy all of that.” We all know the twist at the end, but that’s what I like about that movie; it’s a very spiritual film, but at the same time it’s an excellent piece of horror, because it’s taking that Christian viewpoint of being judgmental and showing how that can bite you in the butt. As opposed to other movies where the shrewd, straight, and narrow people get to live. Not in this movie! That’s what’s so great about it.

G.B.: A really good point. Another thing I like about that movie is the fact that Sergeant Howie [Edward Woodward’s character in the the 1973 original] is actually a pretty fully developed character, he’s very multi-dimensional. Yeah, he’s a judgmental asshole, but he’s also right. And he’s also a good dude who’s just trying to do his job, he’s just trying to save this girl. Yeah, he’s an asshole, but you kind of feel like if you were ever in trouble, Sergeant Howie would be a good person to have along with you. So [The Wicker Man] is not like a “good versus bad” movie, it’s like there’s good and bad on both sides, because the island people… Well, we won’t spoil it for anybody out there, but apart from that, the island people are actually very friendly and happy people, very celebratory of life, very liberated and very feminist, from the standpoint that the sexes are truly equal on this island.

Tony: That’s why I didn’t really care for the [Nicolas Cage] remake. What I loved about the original is it seemed like there was no power structure; yes, there was Lord Summerisle [Christopher Lee’s character in the 1973 original], but he was just the figurehead of the place. He didn’t necessarily say, “I demand all of you to do that,” versus in the other movie, where Hollywood is going, “Oh, let’s have a feminist outlook” and I’m like, “Okay, cool.” But they have one woman ruling everything, which is not really a feminist outlook, that’s just a woman controlling everything. “Oh, we’re gonna have all the men with their tongues cut out, we’re gonna have all this…” And I’m like, “No, no, no, no, no! That’s not feminism. There shouldn’t be any power struggle between the sexes, everybody should be the same, the women can have power and the men can have power. That’s why I like the original 1973 movie, rather than the remake. I like the fact that there was really no no dictator of the island. In any other traditional horror movie, there would have been a clearly evil bad guy; but it’s very ambiguous as to who the true bad guy was, as you pointed out. That’s the good thing about that movie, that’s why I think that movie is something to recognize. Plus, just the fact that it’s also a quasi-musical is something that you need to respect! The music isn’t anything groundbreaking, but this flick is still more dimensional than just, “Stab, stab, stab! You’re dead!”

G.B.: Yeah you’re right, it IS a musical! There are random sequences in the movie where people break out into song and dance. Sometimes naked!

Patrick: What’s wrong with that?

Tony: I mean, it’s basically just a Renaissance Faire caught on tape!

Patrick: [Laughs.] Well, there’s the parking lot. And then there’s the fair part. And then, if you go to the wooded clearing that’s beyond the falconing field, across the highway where everyone sleeps… That’s where it’s real!

Tony: We’ve all been there! [Laughter.]

G.B.: So Patrick, how about yourself? Are there any particular movies – horror- and/or monster-related, supernatural and/or sci-fi – that have really appealed to you during all the years of your walk with Set?

Patrick: Yeah, definitely! So there are two movies that come to mind, and they happen to be my two favorite movies. I’ve always had an interesting relationship with spirituality in general. In some ways, you could make the argument that I am in fact an atheist, because I’ve always felt there is a sort of explanation, if we were to have all of the facts, all the tools, all of the information. I think what we experience with “the supernatural” is valid and exists, and the concept of divinity is compatible with how I’ve always looked at the concept of spirituality as a whole. But I think that much of the mystery and mysticism around our interactions with the Divine, the supernatural, and/or the spiritual comes from a lack of understanding. It’s like we’re looking at a three-dimensional image in two-dimensional space, basically.

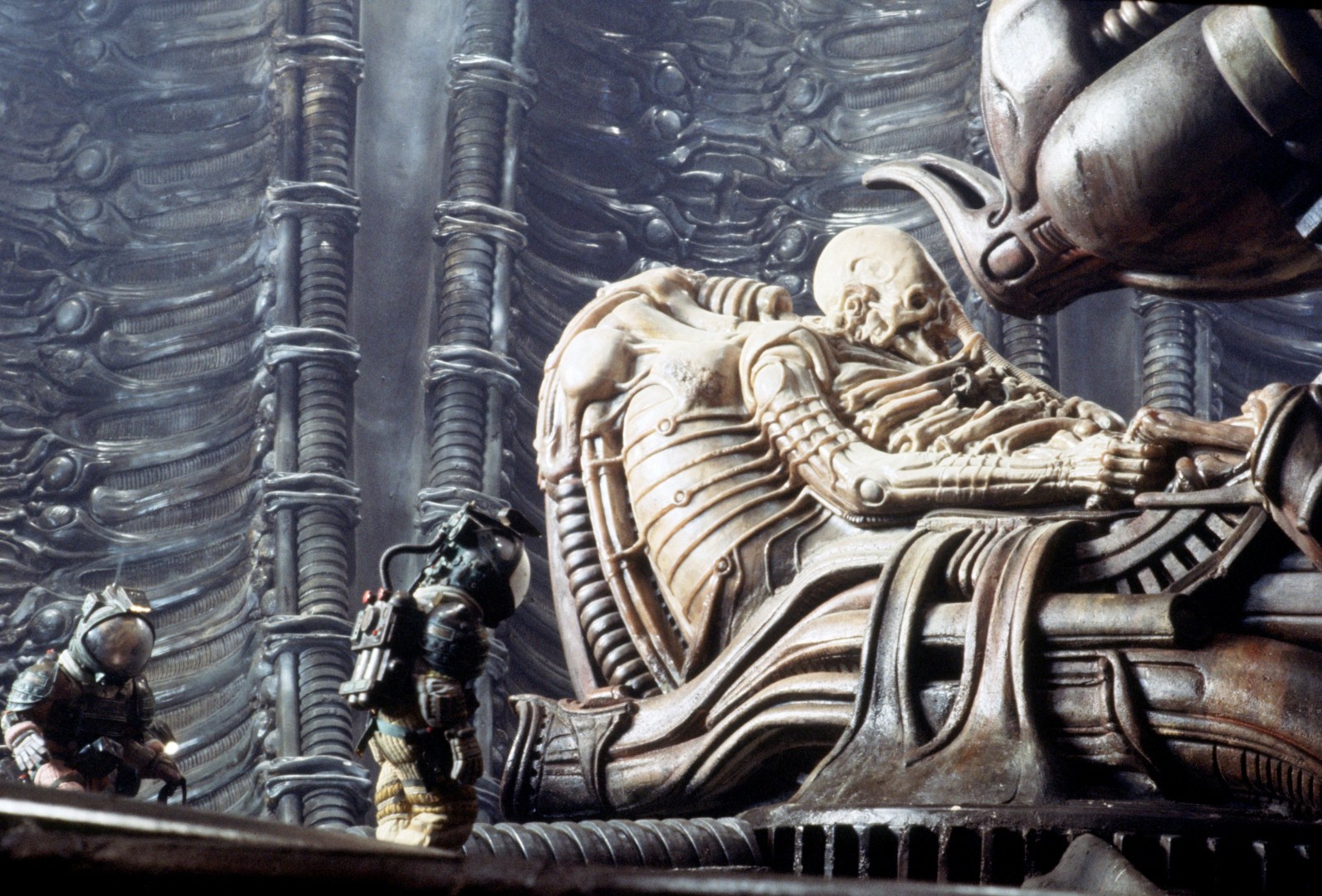

Patrick: So that is partly why these two movies have always really appealed to me. First is the original Alien, the first film from the Ridley Scott franchise; and the second is John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982). First of all, they’re just my favorite movies to watch from an enjoyment perspective, just putting everything else out of the way. But the things happening in Alien are so interesting to me because there is so much mystery, and when you first see the eggs on the Engineer ship, there is a religiosity to the way all that stuff is portrayed. The derelict craft is shot in the same way you would shoot a cathedral or something, with these huge, wide shots of this beautiful interior space that is just haunting, with an architecture that is clearly aesthetic. It is not just mechanical or practical, like the Nostromo (the human spacecraft in Alien), which doesn’t look pretty, doesn’t look good, it looks like an industrial machine floating through space.

Patrick: I think that dovetails so well with my own relationship with spirituality, both as a larger topic, and then when you get into specifics of how the Alien is a kind of “stand-in” for Apep, the Apophis beast. It is horrifying, not because it is malicious, but because it is simply doing what it’s programmed to do, a concept that is later explored in movies like Prometheus (which I enjoy, even though it has nothing on the original Alien). It speaks to the concept of this force that just exists, and there’s nothing we can really do about it existing, all we can do is our best to survive its attacks. To me, Alien is such a pure representation of that, because you have this small localized group of characters who each have their own flaws and experiences, but none of them necessarily deserve to die. In contrast to many horror movies of the 1980s, it doesn’t feel like Scott is saying, “These are bad people and they deserve to die” in any way. If anything, the film paints a picture of working class people who are struggling to make a paycheck, and who are visited by this horrifying daemon and try their best to survive. And there’s nothing you can really do to stop it, except try to get away from it.

Patrick: Ellen Ripley [Sigourney Weaver’s character] is the one who figures out how to survive. One of the things I love about her and the arc of that film is, yes, she is the hero. Yes, she is the force for good in this movie. But she also doesn’t save anybody but herself and her cat. It’s like an examination of hope and resilience and fighting adversity, and of how there is only so much you can do in the face of something that powerful and inevitable. So Alien deals with how the universe works, and with how we emotionally deal with trauma and adversity. There are so many lessons to be had there, that’s part of why that’s always been my favorite film. And The Thing handles a lot of these exact same issues, but from an even darker, more bleak and cynical place.

Patrick: In Alien, the creature is biological and not mystical in any way; but in The Thing, we understand even fewer of the circumstances as to how it got to be there. At least in Alien we know there were eggs in this big ship; clearly these creatures were either captured or created by these people, and that’s why it’s here. So there’s this slight anchor point where you can kind of understand why the thing that is happening to the Nostromo crew is happening. But in The Thing, yes, we know it’s because a UFO crashed; but we can’t even begin to imagine what the world that being came from looks like, and that makes it so much more terrifying. Then you get the scene when they’re estimating the model of how long it’ll take before the Thing conquers the world, and it’s very terrifying, and also particularly relevant for 2020. For anyone who has not seen this movie, it will be a little unsettling, but it’s definitely worth watching this season, because it has a lot of relevance.

Patrick: I also enjoy the way both films approach feminism. Alien is explicitly feminist and is brilliant for that reason. Then you look at The Thing, and it’s a cast that is all male; but the men aren’t necessarily portrayed as these disgusting pigs either. It’s very interesting that John Carpenter was able to take this all-male cast, and when you watch it, you don’t go, “Wow, what an asshole, you didn’t cast a single woman!” It’s not made in a way that feels exclusionary to anyone; this is the situation that we’re in, and all the people in the film feel like they fit, like there aren’t any pieces missing from the puzzle. Which brings us back to your point about the quality, Tony. To me, it doesn’t feel like mistakes were made in terms of representation in The Thing, specifically because everyone fulfills a role in the story that makes a lot of sense. Most movies that are predominantly men or predominantly white or whatever, I look at that and go, “Wow, this is a miss from a diversity perspective,” whether I like the movie or not. But not in this case.

G.B.: The all-male cast actually works to the film’s favor. This is a movie about a slimy, tentacled creature sticking itself into people’s orifices. If there had been women in this movie, considering the time in which it was made… There were other movies from that same period, like Galaxy of Terror from 1982 and Humanoids From the Deep from 1981, that have women being raped by monsters on camera.

Patrick: That is such an awful trope.

G.B.: Yeah, and if there had been any women cast in the film, I feel like at that time, there would have been way too much pressure to make a sexual trope out of it. This movie is already disturbing enough as it is, we don’t need that shit! In fact, The Thing deserves recognition for being one of the only horror movies of the entire 1980s with no sexual exploitation in it whatsoever!

Tony: That’s where I wanna step in with that. I’m glad you brought those two movies up, because those two movies are very interlinked as far as characters go. There is also no sexuality whatsoever in either of them, and you can literally switch the actors in both movies and both would still work. Sigourney Weaver would have played a hell of an R.J. MacReady [Kurt Russell’s character in The Thing], and Kurt Russell would have been an awesome Ripley. The point Dan O’Bannon was trying to make when he wrote the script for Alien was to not have sexuality, so the women and the men can be interchangeable.

Tony: Plus, Alien is basically “Space Rape: The Movie,” where it’s a man getting raped in the beginning. He’s violated and impregnated, and he has to go through what women have to go through from it. If you could boil the whole movie down to one sentence, it would have to deal with the fact that nobody’s listening to this woman [Ripley] who really knows better about these things than any of the men. “Hey, you know the quarantine rules, you can’t let these people in,” she says. But the men say, “What do you know? You’re a woman, I’m gonna let this thing in and we’ll just take care of it, ’cause we’re men and we know how to control this!” But you can’t control it, it’s nature, and the Alien’s only purpose is to penetrate, impregnate, reproduce, and repeat. That’s the whole point of its species. We know from the deleted scenes, as well as from the 1986 sequel (Aliens), that Ripley has a child, which was removed from the first movie to further desexualize everything. There was even a scene where Dallas [Tom Skerritt’s character in Alien] and Ripley have a relationship, but they cut that out too. I don’t know if it was actually filmed or if it was just in the script, but they cut that part out. I’m glad they separated from that, because otherwise we might have walked into Galaxy of Terror territory.

Patrick: Part of why Alien is my favorite film is that horror and science fiction are my two favorite genres, and Alien is both of those things simultaneously. Sexual violence, of any kind, is my least favorite trope in storytelling, period. I think there are stories that definitely manage their implementation of that kind of device to tell a larger story; but Alien does it in such a way that is (to your point, Tony) not so focused on sex, and that is something that so much media fails to deliver.

G.B.: Though I think the argument can be made that Alien is also very sexual, given that it’s essentially about rape.

Tony: I mean look at the [Engineer] ship. I know you compared it to a cathedral earlier, but it also looks like one big, giant vagina.

Patrick: Oh, absolutely.

Tony: There’s all these orifices, and of course we’re getting into H.R. Giger Land, which is Penis City.

Patrick: And The Thing where is very much a film about masculinity and the ways men interact with each other in the world, which makes it feminist-adjacent in a way that many people don’t think about. Frankly it was ahead of its time, because intersectional feminism is definitely a more recent development; obviously there were people laying the groundwork for that in the 1970s and 1980s, and even before that. But intersectional feminism is not just about empowering women, though that is a key part of the feminist conversation. There are also many other pieces to that puzzle, including things like eliminating toxic masculinity, the ways that men are bad to each other, in addition to the ways that men are harmful to women. I think The Thing is very specifically going for that idea, and that is another reason both of those movies have always been connected in my mind, thematically.

G.B.: You’re really right, actually; now that I think about it, a lot of the men in The Thing, their relationships with each other are really quite toxic.

Patrick: Absolutely, yeah. It manages to touch on that toxic masculinity, and even on racism, though with a very light hand, not by beating you over the head with things. It’s such an interesting microcosm of different people and systems interacting with each other, and it’s always made me want someone to make a video game. Not like the one where you’re flamethrowing Thing monsters, but one where you’re managing all of the personalities at play around that crisis, from sort of a pullback perspective. I think the gross creature feature stuff is amazing in that movie, but what really makes it powerful and meaningful is the way in which all of these personalities interact as everything goes to shit.

Tony: I’ve always seen the main issue or the main subject that they’re trying to explain in The Thing as paranoia. Everybody in that movie is hyper-paranoid because you don’t know, “Am I me? Or is me going to be not me? Is my body going to betray me?” and it turns out I was never me this whole time. This to me is a reflection of identity crises in modern society. “Why, I’m supposed to be a ‘man.'” “No, no, no, no, you’re not supposed to be a man.” “Well who am I, then? What am I? Am I not me?” And when you become paranoid like that, some people try to strive for answers, like MacReady, who says, “We’re gonna fix this.” And then there are the people who freak out and pull out their guns to start shooting, because they don’t wanna know, they don’t wanna question what they think they know, because they live in a world of absolutes. “Men are men, and women are women, and I’m not going to break away from this.” But here is this creature that actually is breaking you away from it, because you don’t even know who are what you are when you become super paranoid. And what’s the one thing you wanna do? You wanna find some sort of sanity, you wanna find something that makes you less insane, going back to nostalgia, grabbing on to things from the past that make things seem “real” again. People want some semblance of sanity, but everybody is questioning everything because things are changing, so everybody’s ultra paranoid. And when everybody’s ultra paranoid… What do we gotta do? Oh, we gotta “Make America Great Again.” Okay; so when was it great? 40 years ago? Sure.

Tony: As for the sequel to The Thing – or excuse me, the prequel (2011). Instead of playing up the paranoia, they went with Alien‘s story model instead, with all these men saying, “Don’t listen to the woman, even though she clearly knows what she’s doing.” Still a great movie, but not as impactful as the first one, which is thanks to that theme of paranoia.

G.B.: I think Patrick mentioned earlier – or maybe it was both of you – how the Alien is really just following its natural life cycle, right? Its biological imperative is to rape and reproduce and do the whole thing all over again. The Thing, on the other hand, is clearly an intelligent, sentient being that is capable of building spacecraft superior to our own (and from pieces of trash that it finds around the camp). It’s presumably swallowed countless civilizations. One thing I’ve heard from some other reviewers is how the human characters are hostile to the Thing from the very start, meaning is actions in the story are purely defensive. Well, maybe it was the Thing that came into the story hostile from the beginning, because it certainly doesn’t seem friendly by nature, and even when it’s imitating a human American scientist, it can speak English perfectly, indicating that it understands what is said to it. Yet it never makes any attempt at communicating with the men at Outpost 31 at any point. So for me, whereas the Alien is just an animal, the Thing is actually evil, purely and simply evil.

Tony: Well, it’s basically Apep. Like, “I have one purpose and one purpose only: to destroy. That is my nature.” Do you remember the celestial creature from The Fifth Element where it says, “I eat on purpose, I’m going to destroy…” Well that thing is essentially Apep too, just as The Thing is Apep. It just consumes, it doesn’t do anything else. It’s the “Space Terminator,” it can’t be bargained with, it can’t be reasoned with, we can’t do anything against it, it just destroys, that’s all that it does.

Patrick: Another thing that’s interesting about Alien and The Thing. When you look at Alien, I think it is clearly the product of atheistic thinking. There are parallels with the Apophis beast and probably with other spiritual evils as well. But Ridley Scott makes it very clear at the beginning that the monster is a purely biological, scientific force that was either made or captured by something. It is not a supernatural force that sprang into existence, with the purpose to destroy on its own. And now of course, with the prequels, we know Scott’s ultimate vision for the origin of the Alien species: that it is a product of experimentation and genetic engineering. I think it’s interesting that Scott, who is himself an atheist, would create a story with a beast like that at the center. Whereas the Thing feels more comparable to a supernatural force, with its more mysterious origins. Again, we know a UFO crashed obviously; but there is no reason to assume the craft is actually from the Thing’s home world. We don’t know where it came from, whether it was created in a lab somewhere, or if it is perhaps a literal manifestation of Apep, this beast that’s been riding through space and has just now found its way to Earth. Not to suggest that John Carpenter was trying to make an explicitly spiritual or religious message here at all, of course.

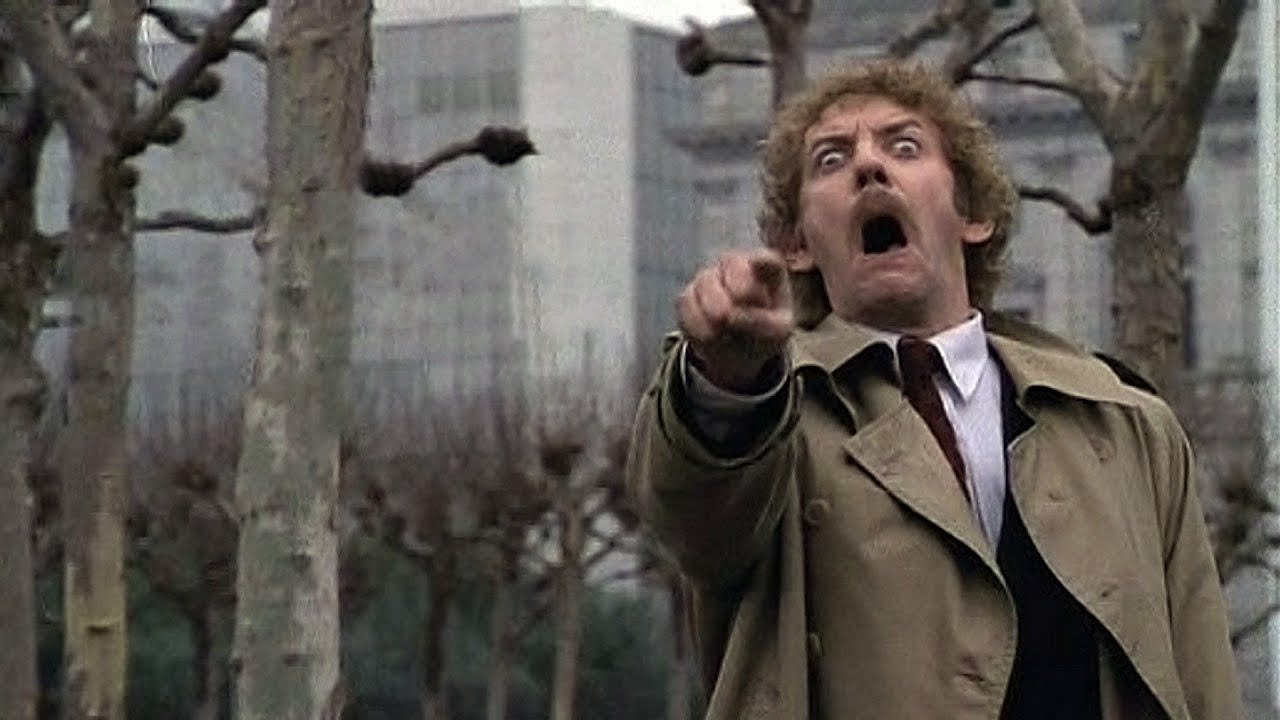

Tony: Continuing down the road of linking spirituality and paranoia with The Thing, and comparing it to what’s going on in the world. Especially here in this time right now, it seems like to me that everybody is paranoid about one side of humanity trying to wipe out the other. For example, we have conservatives scrambling to keep in power, to stomp out whatever progressive or liberal policies they can, to eradicate all of that. And we have the other side, these people who understand the need to grow and change and stuff. Considering this, I’m surprised that Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) isn’t something that people aren’t talking about right now. I’m talking about the 1978 movie; I’ve never actually seen the 1956 original. But the 1970s version is a really good movie to watch right now, given the polarizing times in which we’re living, how it’s “You’re either with us or against us.” It is fucking scary to think, “What if I wake up and I’m one of them?” And it’s the same message with The Thing. What if you wake up and you’re one of THEM? All three of us see ourselves as very tolerant people, but what if we wake up one day and WE’VE become the aliens, the invaders, the monsters? That is some super scary shit.

G.B.: You mean the version of Body Snatchers with Donald Sutherland, Leonard Nimoy, and Jeff Goldblum, right? That’s a good one!

Tony: Yeah!

Patrick: Such a good movie. At the same time, I’m hesitant to watch it, because November 3 is coming around. Having re-watched The Thing many times, my opinion is that MacReady is not the Thing, and was never assimilated at any point. I think he’s human even at the end, and I think they kind of explicitly point to Childs [Keith David’s character] as being infected, though that is a debate that will rage for the ages. But when you compare it to political beliefs and a change in one’s interaction with sociopolitical issues over time, one of the reasons why I feel so confident in MacReady not being the Thing is that he always has an analytical view of the situation, and he is very smart in how he interacts with the potential for infection and the potential for getting turned into the Thing. I see MacReady as a model for staying true to your innermost convictions; he remains himself no matter what, just like I am very confident I will never become politically conservative.

Tony: That’s a great point. But let’s look at what happens with Blair [Wilford Brimley’s character in The Thing]. Okay, so we don’t know when Blair was eaten by the Thing, exactly, but look what happened when he discovered the truth of how long it would take for the Thing to infect the entire world. He just goes berserk. It depends on how you react with it, but some people just can’t handle that kind of information, they literally go crazy. If we sat down and were shown a model telling us the human race will go extinct in 22 years, how would we react to that? If you’re like MacReady, you take an analytical route and go, “Alright, well I’m just gonna do the best I can do, and keep learning and keep going.” But if you’re like Blair, you just flip the fuck out and start diving into paranoia, like those people in the QAnon movement, and you start scrambling and going crazy.

Patrick: Yeah. I certainly don’t have the answers when it comes to helping the Blairs of the world…

G.B.: There have been several times this past year when I felt like I was almost turning into Blair!

Patrick: I have zero tolerance for things like QAnon; but at the same time, I don’t have the answers for someone who is scared. And you’re right, Tony; whether Blair’s reaction to the Thing is a “reasonable” response or not, it is still a real response, a valid experience that can occur when we see things that horrify us. My partner and I talk frequently about how much easier it would be to just not know anything and not care about anything outside of our media bubbles. So I am hesitant to ascribe a reaction like Blair’s to any kind of moral or ethical weakness.

Tony: Some people like to take that and make that their shiny new shield on their chest. “Well, look at me, I’m more put together than you!” And that just feeds off the negativity. As weird and as cheesy as it sounds, many of those people just need a fucking hug, man. OK, you’re scared! I get it. But there’s no need to act like a buffoon!