The word devil is really just as vague and complex as the word God, holding multiple meanings across the world. So when we “speak of the devil,” just what in hell are we actually speaking about?

Accusing someone of “worshiping the devil” is the easiest way to discredit their faith and beliefs. Pagans are no strangers to such accusations, and this is doubly true for Setians, Lokeans, and others who walk with the so-called “powers of darkness.” But the word devil is really just as vague and complex as the word God, holding multiple meanings for different people and cultures across the world. So when we “speak of the devil,” just what in hell are we actually speaking about?

The figure identified as “Satan” in popular culture is not 100% Christian in origin, but something more like a schizoid Frankenstein monster patched together from various religious traditions over the centuries. The ideas that people have about this figure today are not only influenced by biblical teachings, but by generations of militant Christian deculturalization as well. Most accusations of “Satanism” turn out to be nothing more than non-Christian religions upon closer inspection (or in especially ludicrous cases, they turn out to be any Christian denomination apart from one’s own). There are also several different versions of “Satan” referenced throughout popular culture, and people never seem to know which of these variants they happen to be discussing at any given time. The situation gets even more complex when we account for actual Satanist beliefs about the devil, which is a whole other kettle of elephantfish.

Satan as the Heavenly Prosecutor

Introduced to us in the biblical book of Job, this version of Satan is far less subversive than people commonly know. He is but a servant of the Israelite God, only committing the harms his maker allows him to commit. Tormenting humans, tempting them, and testing their faith in Yahweh is not an act of rebellion, but a service he provides at his maker’s behest. As such, the purest distillation of Satan in my opinion is simply the shadow side of monotheism itself. If the entire point of such belief is our submission to just one God (and our strict avoidance of all others), then naturally someone is needed to periodically test that allegiance. The way I see it, the Old Testament Satan represents the dark side of Jehovah himself; there is no other role for a devil that makes any theological sense in a purely monotheist context.

While I accept the Christian God as being ontologically real, I remain skeptical of his alleged omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, and omnibenevolence. I believe Yahweh and Jesus Christ both exist, but they are just two more Gods occupying our shared multiverse, neither more nor less important or perfect than any other divinity in objective reality. I accept they are of central importance to their own followers, and I can see how Satan the Heavenly Prosecutor would figure largely in their personal value systems. But to “worship the devil” in this context seems equivalent to accepting a payoff from Mr. Slugworth, then learning the slick bastard was really working for Willy Wonka the whole damn time (but now you can’t have any chocolate!). In my experience, this version of the devil isn’t venerated by anyone (not even by real Satanists); people are only ever accused of trafficking with him by monotheists.

Satan as a Serpent, Dragon, or Gnostic Figure

In the book of Genesis, the first man and woman are deceived into disobeying Yahweh by a talking snake. Many people think of that snake as Satan, but it was never identified as such until New Testament times. By that point, Judaism and Christianity had both been influenced by such combat myths as the Babylonian Enuma Elish. These are tales of divine warriors battling monstrous serpents or dragons to create or save the world, and Set’s daily pre-dawn battle with Apep is just one of many variants. Judaism already developed its own variant of this story in the figure of Leviathan, a sea monster that represents all human and supernatural defiance of Yahweh. (Leviathan originally comes from Phoenician mythology, in which it is sent to attack the Elohim by the daemon Yamm, who is battled by Set in the Edfu Texts.) So by the time Roman emperors started feeding Christians to lions for sport, the biblical idea of the Genesis snake had been firmly conflated with the polytheist Chaos Serpent, which seeks to end the universe. Hence the depiction of Satan as an apocalyptic “great red dragon” in the book of Revelation.

The Gnostics were Jewish and Christian heretics who lived during New Testament times, and who deviated from monotheism. They believed in not one but two Gods: a benevolent God of pure spirit who transcends the physical universe, and an evil material God who keeps our souls trapped and miserable here on earth. Some viewed the Genesis snake as a messiah sent by the good God to free us from the prisons of our flesh. Mainstream Christians decided these people were “Satanists” for this reason, and some real life Satanists actually take their cues from Gnosticism as a result.

To be honest, I find Gnosticism troubling. It teaches that nature is soulless, and that human souls are alien not only to their surroundings, but to their own bodies as well. Such anti-cosmicism is really in vogue among left-hand path circles, which often re-define the Chaos Serpent as a kind of Gnostic savior figure. There are even Setians who engage in this, conflating Set with Apep (which is predicated on Set’s demonization as the Greek Typhon circa 712–323 BCE). With all due respect to these people, I believe Setianism is about revering a God who is a part of nature, and who is absolutely essential to how the cosmos perpetuates itself. Qliphothic diabolism, on the other hand, is the adoration of something external or even hostile to nature (which contradicts the entire premise of honoring a Pagan God in the first place). Setians can combine their love for Set with any other spiritual traditions they like, and we do not need each other’s approval to do so. But to my mind at least, Set shares more similarities with Jesus Christ, the archangel Michael, and even Jehovah in this particular context (Aberamentho!) than He does with Satan.

(Mind you, I don’t believe Set is “angered” or “offended” by anyone identifying Him with the Serpent. He’s a big god, He’s got a thick proverbial skin, and I’m sure He has His reasons for interacting with folks like Kenneth Grant and Michael W. Ford. I fully admit I am likely more bothered by this subject than Set is Himself. My intent here is not to “shame” anyone into ditching their copies of Nightside of Eden or Sekhem Apep, though I encourage people to at least consider the idea.)

Satan as Antichrist or the Great Beast 666

There is a major biblical distinction between “the Antichrist” and “the Great Beast 666,” which is called Therion in Greek. Antichrist is basically the spirit of Christian hypocrisy itself, or the impulse to do un-Christian things in Christ’s name; Therion is the archetypal evil tyrant who brings disaster upon his own nation. The latter goes back to the primeval origins of human government, but Christians first met him in the guise of the Roman emperors, whom they considered to be satanically possessed (and for good reason). Somewhere down the line, Antichrist and Therion were blurred together into the same popular image: that of the devil’s half-human offspring, destined to set the world ablaze.

In this context, Satan is a metaphor for both Christian and political corruption. Anyone can be deceived by a corrupt politician, including Pagans; but the idea that we are out to cause the downfall of human civilization is just ridiculous. And accusing us of worshiping Christian hypocrisy makes no sense at all. People like Paula White, Creflo Dollar, Kenneth Copeland, Rod Parsley, and other “prosperity gospel” televangelists do a much better job of driving people away from Christ than Pagans ever could. No one does a better job of publicly glorifying Antichrist than these false ministers of Mammon.

As for Therion, there are reasons for thinking he might be enemies with Ishtar, who is my Holy Mother Goddess. Part of Ishtar’s role in ancient Babylon was to empower the kings and punish them severely if they failed to take good care of their people. Especially shitty rulers were offered as blood sacrifices to Her, demonstrating that She does not suffer tyrants lightly. Even the Bible seems to agree that the Great Beast and the “Whore of Babylon” despise each other (Revelation 17:15–18). So if someone accuses me of “worshiping Satan” in the sense of supporting the tyrannical persecution of Christians, they couldn’t be further from the truth. As a Pagan, I would prefer to live in a world where no one is ever persecuted for living the life they want to live, neither Pagans nor Christians nor anyone else.

But while Therion is a symbol of tyranny and persecution for Christians, he more often represents freedom, liberty, and self-empowerment for Satanists. This interpretation is not biblical, but is influenced by the teachings of Aleister Crowley, who actually claimed to be Therion incarnate. (Considering how oppressive and manipulative a person he was, I’m inclined to agree that Crowley was a perfect avatar for the Final Tyrant.) If we define Therion in a strictly Thelemic or Satanic context, I can see how the figure might be used to exemplify key Setian values like autonomy and self-ownership. But if we define him in the Christian context, I consider him anti-Setian and want nothing to do with him.

Satan as a Fallen Angel (“Lucifer”)

The devil’s most well-known origin story is that he was originally an angel in heaven named Lucifer. He tried to usurp his Creator’s throne, was cast down from heaven for his pride, and now rules his own kingdom down in hell. This story does not appear anywhere in the entire Bible; it’s actually a polytheist theme that was not fully absorbed into Satan’s demonology until the medieval era. (The reference to “Lucifer” in Isaiah is a shoddy Latin translation; the original Hebrew text refers to a mortal Babylonian king.) Prior to this, Lucifer was one of many polytheist Gods identified with Venus, the Morningstar. The astronomical behaviors of this planet—keeping near the horizon; shining brightest at twilight; “defying” the sun by appearing just before dawn—led people to associate it with several uppity Gods who subverted their elders. Each of these Venusian powers is linked with fire and fertility, as well as with death and resurrection. Females like Aphrodite and Inanna are usually successful in their rebellious designs, but their male counterparts are more often ruined and forced into exile, which brings us back to Lucifer.

There is no direct relation between Set and the Lucifer myth, but some people draw parallels between the two anyway. Set’s demonization can be likened to Lucifer’s fall from heaven; and then there’s the theme of Set defending Ra from Apep in the Underworld just before sunrise. The idea of a rebellious Red God facilitating the sun’s rebirth can be linked with the theme of a “fallen angel” heralding the dawn. I must admit, however, that these associations are a bit of a stretch for me personally. Set has little to do with Venus, and most other divinities who do are “dying-and-rising” figures. Set never dies, and He never “falls down” into the Underworld either; He just travels there every night with the Creator to serve as Ra’s personal bodyguard. This dynamic doesn’t really jive so well with the “Fuck God, I’d rather rule in hell!” attitude that Lucifer more often exemplifies. In my opinion, Set and Lucifer are two completely unrelated figures, though I can see how Big Red might bond with the latter as a drinking buddy.

The truth is that when I hear or read the word Lucifer, I think of ISHTAR and not Set. Lady Morningstar appears in my mind’s eye as a beautiful angel with raven-black hair and wings, shining with unbridled fury. I can’t help but root for Her as She tricks Ea into giving Her the powers of civilization; as She descends into the Netherworld to face Her sister Ereshkigal; as She slays Her ungrateful husband Tammuz to take Her place in hell; and as She rages against that insolent megalomaniac, Gilgamesh. Ishtar’s resemblance to the biblical “Whore of Babylon” is famous, but She also resembles a female Lucifer who (unlike the more popular male version) generally succeeds in getting Her way. So if anyone accuses me of “worshiping Lucifer,” my first reaction is not to deny the accusation, but to correct it. (“My Angel of Light is a Lady, so if you absolutely have to call Her something in Latin, it really ought to be Lucifera!”)

Satan as a Horned God

By far, the most well-known version of the devil is that of a wooly goatman who frolicks with witches in the dead of night. This motif developed well after the Protestant Reformation, when the European witch hysterias reached their apex. It has no biblical basis, but is instead a synthesis of Protestant reactions to Judaism, Catholicism, several medieval Christian heresies, and numerous polytheist folk traditions. Much has already been said of how the devil’s horns and cloven hooves were appropriated from the Greek satyr God Pan, who similarly enjoys frolicking with nymphs at night. But there are actually several Gods who were absorbed into this devil, not just Pan. Virtually every culture has acknowledged some kind of nocturnal horned God who digs raunchy, bacchanalian rites; and it is here that I experience the most trouble with my surrounding culture. As with most people, this is the “Satan” I always think of first whenever anyone brings up “the devil.” Society has drilled it into me since birth that horned, hoofed goatmen are supposed to be “evil”; and yet this imagery is quite sacred and inspirational to me personally.

Set is just one of the many Gods whose imagery was appropriated for this version of Satan (thanks to the Coptic Church). We see this in Set’s affinity for nighttime, the color red, and such horned Artiodactyla as oryx and antelope. We can also see it in His attraction to Goddesses who defy conventional gender roles (Taweret, Ishtar, Nephthys, Anat, etc.). And then there’s the fact that He is the God of wilderness, deserts, and other places beyond human civilization. From the moment I first met Him back in 1997, I have always felt compelled to honor Set out in the woods at night; so I identify with the Horned God image pretty strongly. For this reason, my brain does two things whenever people talk about “Satan” around me (whether it’s in conversations about religion, horror movies, or heavy metal music):

- It immediately conjures up a Horned God image.

- It immediately translates the name Satan into SET.

Some claim that the Hebrew word Satan is etymologically derived from Set’s name (via “Set-Hen” or some variant thereof). There is no evidence to support this assertion; yet it speaks to a very real Setian emotional experience. Some of us (myself included) first come to Set without fully understanding who or what He really is. Some don’t even know that much about ancient Egypt when He first calls them; they might realize there’s this spooky nocturnal Red God speaking to their souls, but that’s it. Setians in these situations often have little choice but to conceptualize themselves as “Satanists” when they first answer the call. (What the hell else are we supposed to do when society tells us that’s exactly what we are, and we don’t know any different?) Some may continue to identify as such for life; remember, Setian beliefs are not limited to Kemeticism, but can also intersect with other religious traditions (including Satanism and Christianity, both). Still others may discard “Satan” into the proverbial wastebasket once they develop a more Kemetic understanding of Big Red. (I can’t tell you how much better I felt once I achieved this for myself.)

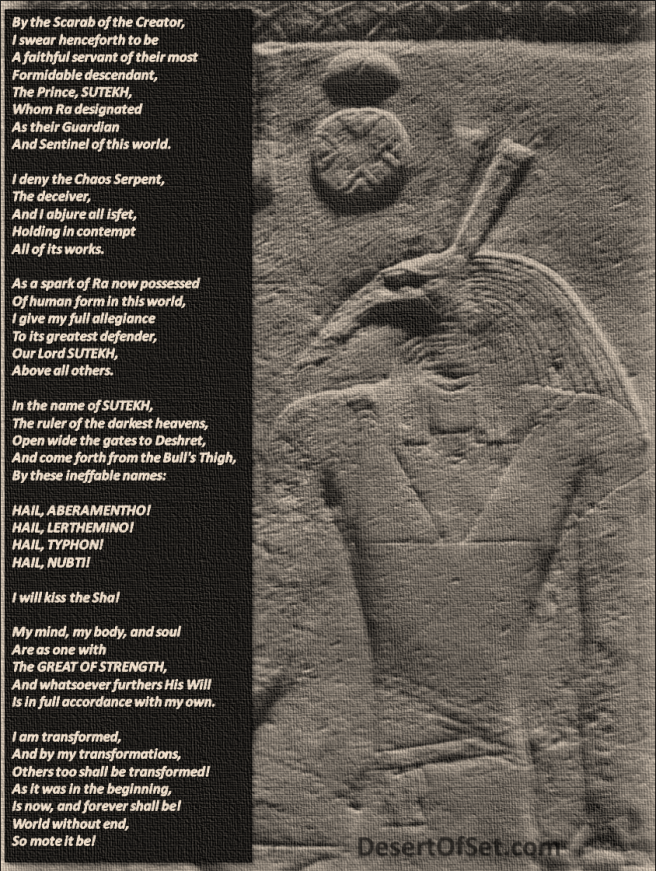

Here’s an example of what I mean about my brain “translating” the Horned God motif into Set. One of my favorite bands is the Danish metal group Mercyful Fate, fronted by King Diamond. One of their greatest songs is “The Oath” from their 1984 album, Don’t Break the Oath. The lyrics of the song are partially adapted from Dennis Wheatley’s 1960 novel, The Satanist, which features a so-called “black mass.” But whenever I listen to this song, here is how my brain translates the lyrics:

Here is a link to the original song by Mercyful Fate, for anyone who might be interested.

It might seem odd that anyone would appropriate Satanic symbolism for a Pagan God (as opposed to simply rejecting such iconography altogether); but the way I see it, this is a perfectly logical thing for Pagans to do in our contemporary environment. Christians came along, wrested control of our religious narratives, and indoctrinated entire generations into thinking our various horned Gods are really “the devil.” So it seems only right that Pagans, in turn, should appropriate “the devil” and turn it back into something positive that we can use for our own purposes, as demonstrated in the graphic above.

Satan as a Romantic Anti-Hero

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, serious belief in Satan had waned throughout the West, with the figure seldom appearing in any religious context. During this period, he was more often seen in works of art, literature, folklore, and political philosophy. Several artists, writers, and even radical leftists invoked the devil in their works as a sympathetic rebel against tyranny (personified by the Christian God). John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost is only the most prominent example; others include various works by William Godwin, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, and even Mark Twain. And since the point of this artistic movement was to encourage freethinking (for which Satan was thought to be the perfect symbol), it has since become known as “literary Satanism.”

It always confuses people to learn that mainstream Satanist groups like the Church of Satan and the Satanic Temple don’t actually “worship the devil” per se, but are atheists. This makes a great deal more sense when we remember that such groups are really descended from the literary Satanism movement. Anton LaVey didn’t take his Satan from the Bible; he drew him from Paradise Lost and other similar works. The point is not to be a “devil worshiper” but to actually become an arch-rebel oneself, in the flesh. While the chosen terminology might frighten outsiders, the whole thing amounts to little more than thinking rationally, challenging authority, and championing personal liberty, which I think are values most people can agree with. There are some things about mainstream Satanism I find annoying (e.g., I can do without Peter Gilmore’s near-constant assertion that all theists are categorically insane); but on the whole, I think it’s a pretty reasonable way of looking at the world (“Satanic” or not).

Returning to the $666 Million Question: “Do You Worship the Devil?”

When Pagans are accused of “worshiping the devil,” our typical response is to say “We don’t believe in Satan.” But as I have discussed here, the word devil is just as culturally loaded as the word God. If we define Satan in strictly biblical terms, then no, most of us do not believe in “the devil” at all. But when most people discuss this figure (including Christians), they are referring to one or more non-canonical tropes, not to the original biblical concept. And whenever this is the case, things become much less cut-and-dry. Many of us worship a horned God and consider ourselves to be witches (myself included). Some pray to Venusian deities who can be read as prototypes for Lucifer (again, myself included). And there are even people who actually glorify the Chaos Serpent (myself NOT included, thank you very much). Some Pagans who fit these descriptions actually identify as Satanists too (or as Luciferians). Who are we to tell them they aren’t welcome in our community, so long as they live and let live? If we can accept Christopagans and Jewitches in our subculture but not Satanists, then we are hypocrites.

While more Pagans are fortunate enough to be raised in Pagan families today, the majority of us are converts from other faiths, and most of us were raised either Catholic or Protestant. “I still have a soft spot for the Catholic Church” is a common sentiment I’ve heard from Pagans who were raised Catholic, and this is likely because Catholicism absorbed quite a bit of Paganism into itself over the centuries. Blooming Pagan teenagers in Catholic families are already exposed to countless Pagan ideas, from venerating a Goddess (the Virgin Mary) to celebrating the three nights of Samhain (All Hallows’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day). But the entire point to Protestantism is to purify Christianity of all such Pagan influences, consigning them to the devil. So Satan is often the only Pagan thing many Protestant kids are exposed to when they are young. And when a Pagan first blooms in such surroundings, it can be much more difficult to “unlearn” the things they have been conditioned to believe. Going from “hailing Mary” to “hailing Hathor” is one thing, but going from “fearing Satan” to “loving Pan” is quite another.