Here I geek out for a bit about my vote for “the scariest monster movie ever made,” and I draw some parallels between the themes of this film and my beliefs as a Setian.

John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) wins my vote for “the most frightening monster film ever made.” Its unique history begins with a science fiction author named John W. Campbell, Jr., who wrote a short story in the 1930s called “Who Goes There?” It features a team of scientists who discover a spaceship buried beneath the ice in Antarctica. They dig out the ship’s pilot and bring it back to their base, thinking it’s just a frozen fossil. But once the creature thaws out, it springs into action and starts terrorizing everybody. Then it’s discovered that the Thing (as this hostile invader comes to be called) not only digests its prey, but can manipulate the cells of its body to shapeshift into whatever it has eaten at will. The men at the research facility soon learn this applies to human beings as well as to animals, and they descend into violence and paranoia as they accuse each other of being the monster. That’s when a guy named R.J. MacReady takes charge of the situation and figures out a way to determine who’s who.

In 1951, the great Howard Hawks decided to make a film adaptation of “Who Goes There?” that was renamed The Thing From Another World. This was the first of what would later be called the “atomic horror” films, in which humanity is threatened by giant radioactive animals, mad science experiments, or Commies from outer space. For whatever reason, the setting of Campbell’s story was switched from Antarctica to the North Pole, and the shapeshifting alien was re-conceptualized as a blood-drinking humanoid made entirely of vegetable matter. (One character actually refers to it as a “super-carrot.”) Despite these drastic changes, The Thing From Another World is one of the greatest sci-fi/horror films ever made. It has lovable and humorous characters, some intense machine gun-paced dialogue, and several suspenseful scenes that still hold up today. The film influenced an entire generation of filmmakers, including John Carpenter, who loved it so much that he has his characters watching it on TV in Halloween (1978).

When Ridley Scott’s Alien came out in 1979, it made a shit-ton of money. Suddenly, big-budget creature features were in vogue. That’s when Universal Pictures acquired the rights to produce a remake of The Thing From Another World. I believe monster movie remakes are generally a horrible idea, and that they should be avoided as much as possible. But in The Thing’s case, this rule does not apply. Part of what makes the Carpenter film work is that the original 1951 version deviated from its source material so much. While it’s still about an alien terrorizing people in the snow, Hawks’ monster and human protagonists are totally different. (There isn’t even a “MacReady” in Hawks’ film.) So John Carpenter and his team decided to make this new film a more faithful adaptation of the original Campbell story, which had never been properly adapted for the screen before. For this reason, the 1982 Thing is radically different from its 1951 predecessor, which caught many audiences off guard at the time. Most viewers in 1982 were expecting to see something fairly light-hearted and optimistic, much like the 1951 original. They weren’t expecting to see anything quite so bleak, depressing, or nightmarish as what they were given.

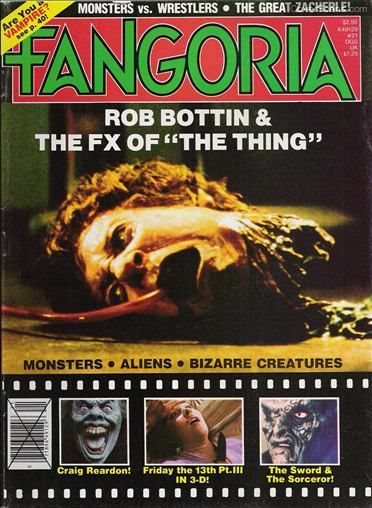

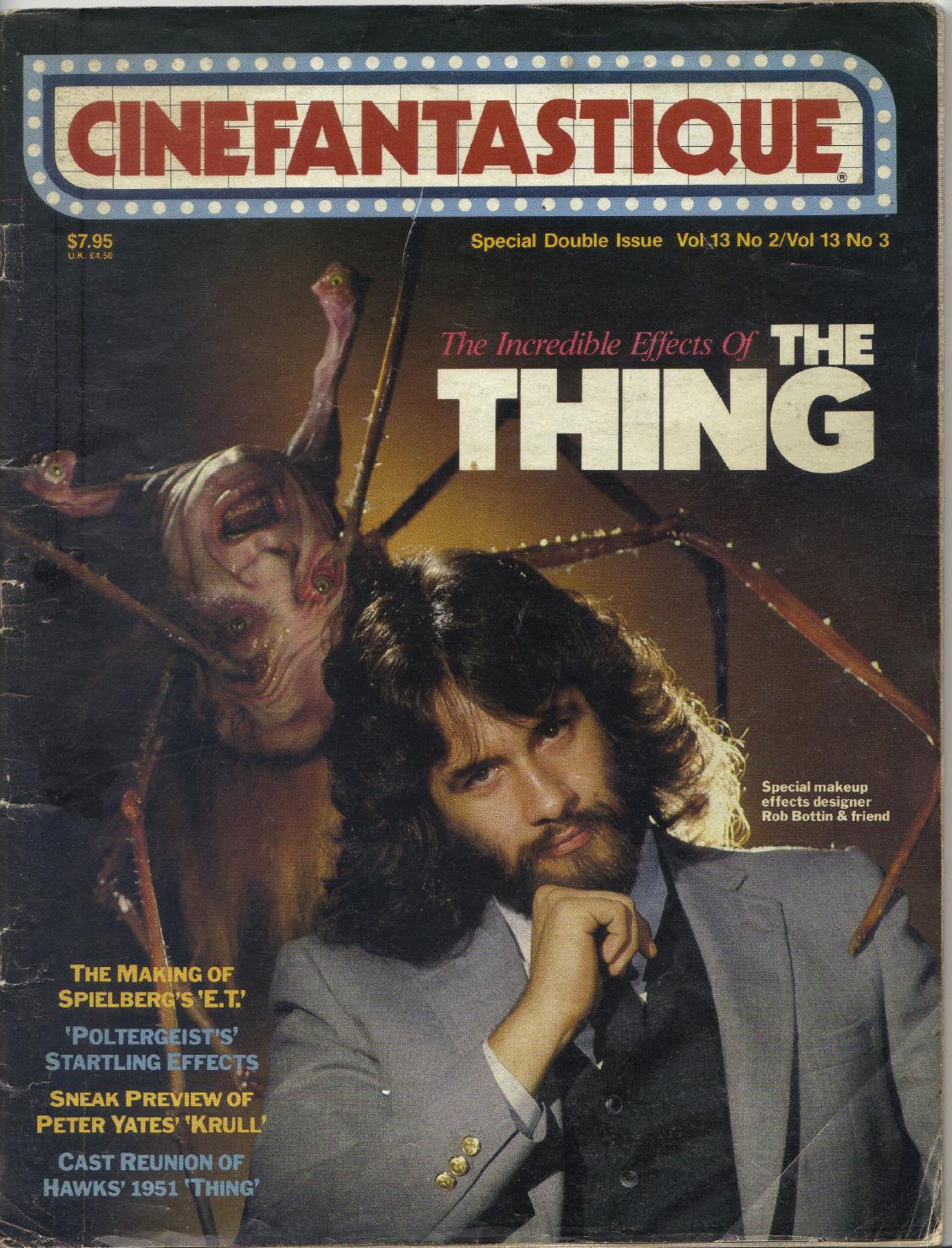

The Thing boasts some of the most convincing makeup and creature effects you will ever see; in fact, the effects are perhaps a little too convincing. It’s hard to believe the monster is really just a bunch of puppets, but creature effects wizard Rob Bottin put so much of his heart and soul into them that they still look superior to most CGI effects that are used in films today. Unfortunately, audiences in 1982 just weren’t ready for what they saw. The most well-known sequences of the film are those in which the monster devours, digests, and transforms into its helpless prey. Globs of slime, blood, and stinking pus are splattered all over the walls while men are physically disfigured into shapes that defy all rational categorization. These scenes are grisly, revolting, and very hard to sit through, but the amount of imagination put into them is absolutely staggering—even by 2019 standards. The effects are so realistic and excessive, however, that people just went apeshit. Film critics rabidly accused John Carpenter of being “a pornographer of violence,” and he was practically blacklisted by Universal. Indeed, audience reactions to The Thing during its original theatrical run almost ended Carpenter’s career entirely. How ironic, then, that the film would be re-evaluated by fans and critics over the following decade, to the point of being accepted today as Carpenter’s very best work. And the sheer number of other media properties it has influenced (e.g., Dead Space, The Mist, Resident Evil, Slither, Stranger Things, The X-Files, and practically everything on Guillermo del Toro’s resume) demonstrates that The Thing has had a major impact on popular culture.

I love it that this film features an ensemble cast, which means there are multiple principal actors who are given roughly equal amounts of screen time. The great thing about ensembles is that the actors will rehearse together and develop a chemistry you just can’t get anywhere else. The players in this film are all well-seasoned stage actors, to boot. While the script is rather skimpy on character development, the actors make up for this with all the neat visual cues they worked out together. We can tell that Clark (played by Richard Masur) is much more comfortable with the dogs at Outpost 31 than he is with the other men. When he learns that one of the other men has died, he shows little emotion apart from fear; but when he learns that one of his dogs have been killed, he becomes upset and mournful. We can also tell that Garry (played by Donald Moffat) resents being the leader of the group, because he always has a reluctant look on his face whenever he has to take charge. It’s obvious from their expressions that none of the other men take his authority very seriously, and Garry is also much quicker to relinquish his authority to MacReady (played by Kurt Russell) than most leaders would be. Despite having lived and worked together for some time, the men at Outpost 31 seem to know practically nothing about each other. They’re alienated from the rest of the world by living in Antarctica, but they’re also alienated from each other by their own apathy and disinterest. Since the Thing can imitate any life form perfectly, neither the characters nor the audience can ever tell who is who. This is made even more horrific by the notion that these people never really knew or cared about each other that much in the first place. The Thing doesn’t have to work very hard to push them into a panic, for they are already in a position to fear and loathe each other when the film begins. If their humanity is all that really separates these men from the Thing, that wall of separation must be frightfully thin.

One criticism I sometimes hear about this film is that the actors are all male; there are literally no women to be seen anywhere. I can understand why this bothers some viewers, but I actually appreciate the all-male cast for a couple of reasons. First, there’s this unspoken rule in Hollywood that monster movies must always have some kind of heteronormative sex appeal; there must be gorgeous hot women removing their clothes for the male viewers, and there must be one dude and one dame who make it to the end so they can presumably fornicate once the credits roll. The Thing dispenses with this “wisdom” by not even allowing the subject of sex to be breached in the first place. Furthermore, this movie is about a slimy tentacled monster that likes to rip people’s clothes off and insert itself into their bodily orifices, which is already disturbing enough as it is. If there had been any women in the film, I guarantee they would have been sexualized; there were other films being produced during the same era that indulged in this exact form of sexual exploitation (including 1980’s Humanoids From The Deep and 1981’s Galaxy of Terror, which both feature monsters raping women on camera). Indeed, The Thing is one of very few 1980s monster films that doesn’t feature any kind of sexual exploitation at all.

I think another reason audiences hated this film upon its original release is that it’s just so Gods-damn bleak. Even the goriest slasher movies of the 1980s usually had some kind of comic relief or silliness in them; but aside from some brief touches of humor here and there, The Thing offers no such relief. Nor does it offer any clarity with regards to its conclusion. Audiences prefer happy endings in their monster movies, but they can also handle bad or scary endings, as long as they’re clear-cut. The evil can either win or be defeated, but it must clearly be one or the other. The Thing throws this archaic rule right out the window, for its ending is completely ambiguous, leaving us uncertain as to how the story really ends. And that is something most people just can’t seem to handle in a movie. Mind you, I can understand why; it bothers me that we never find out exactly who won or who survived. But that’s what makes the ending work; it continues to bother you and haunt you long after the credits have rolled. (I still wake up in the middle of the night every so often, wondering: “Who’s really human at the end of The Thing?!”)

In my opinion, the titular beast is an even better representation of Apep, the supreme enemy of all Gods and creatures, than H.R. Giger’s Alien. The xenomorph can be pleasing to look at, with its shiny symmetrical body and its humanoid shape; but the Thing is absolutely horrible to observe in either of its myriad, spidery forms. And while the Alien is just an animal that seeks to eat and reproduce according to its primal dispositions, the Thing has assimilated countless worlds and species into itself. It is sentient, can build and operate spacecraft far superior to ours, and is totally capable of communicating with humans. (It speaks perfect English whenever it pretends to be an American scientist.) If such an ancient intelligence had any goodness in its heart, it would try to reach some kind of understanding with the men of Outpost 31 at least once. Yet the Thing never bothers to communicate with the men at all (apart from when it imitates them). This suggests that the creature is purely and simply evil. It deliberately terrifies, harms, and divides other sentient beings with a malevolent self-awareness, and it will settle for nothing less than the extinction of all life upon this earth. If that doesn’t sound like Apep, I don’t know what does.

But there is much of Set to be found in this film, as well. Most of Antarctica is actually a polar desert, since there is little to no precipitation or vegetation there. A “desert” is technically defined in terms of how dry a given location is (rather than how hot), and Antarctica is drier than a bone; very little rain or snowfall ever occurs across the entire continent. Given that The Thing’s premise is essentially a modernized combat myth (in which a heroic warrior fights a gruesome monster to save the world), it’s only fitting that this battle should unfold in an ecosystem that falls under Set’s jurisdiction. And in Egyptian mythology, Apep has a paralyzing stare that freezes most of the Gods with fear, rendering them motionless and inert. Set is the only God who is immune to this; hence why He was chosen to serve as Ra’s Champion against the beast. Perhaps it is no accident that when most of The Thing’s characters come face-to-face with their extraterrestrial assailant, they too become motionless and inert. MacReady is the only one who seems unfazed whenever he sees the monster; he even has the nerve to taunt it right to its ugly face. (His best line is when he tells the creature, “Yeah? Well fuck you too!”) Indeed, he exudes the time-honored Setian attitude of “I’m-just-saving-the-world-so-I-can-get-back-to-drinking” quite nicely.

As a Setian, I believe autonomy is divine—a gift not only from the Gods in general, but also from Set in particular. He is the God of otherness, the principle that makes it possible for everyone to exist as individuals with distinct identities. The word “other” often bears a negative connotation in common discourse, as when we speak of societies “othering” minorities. But we are all others to each other, even in the cultures and cliques we call our own. Otherness is a good thing, something to be cherished and celebrated, because it enables each of us to determine ourselves as unique sentient beings. It is not otherness, but the fear of otherness which poses the ultimate threat to our existence. As frustrating and confusing as Set can be for the other Gods, even they must accept Him as a necessary force in this world; for without Him, they would be frozen by the Serpent’s stare and absorbed into its vacuum. They would cease to have selves and be dissolved into the void forever. Otherness has been painted red and given devil horns for Set knows how long, but true evil is the desire to exterminate otherness, to eliminate whatever is different. And the Thing is a perfect representation of such erasure. Just like Apep, it is homogeneity personified, hating whatever is not itself and robbing its victims of their innermost identities and souls.

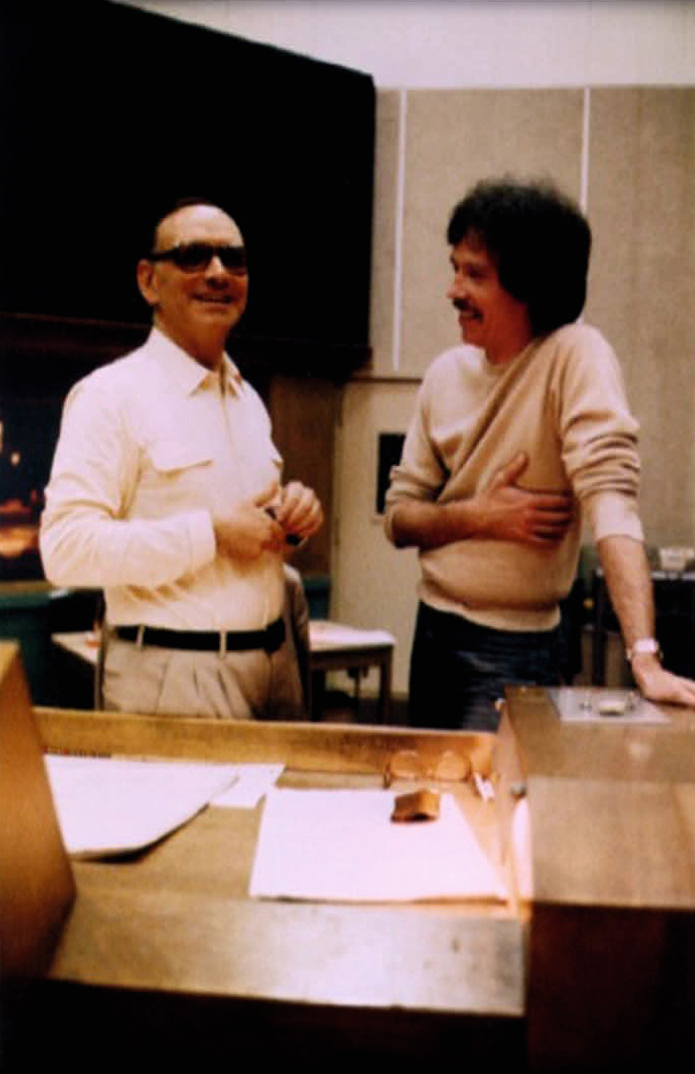

Ennio Morricone (left) and John Carpenter (right), circa 1982.

John Carpenter is legendary for scoring most of his films himself; but for this venture, he recruited the Italian composer Ennio Morricone (who is most well-known for scoring 1967’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly). Morricone wrote about 50 minutes’ worth of orchestral music, approximately half of which would never be used in the final cut. Supposedly, Carpenter had difficulty deciding where to insert certain pieces of music into the film. So while The Thing was in post-production, Carpenter went to the recording studio and hammered out some incidental pieces to make up for the material he couldn’t use. As a result, about 90% of the music in The Thing is Morricone’s work, while the remaining 10% consists of Carpenter’s trademark electronic drones. The theme song (which is actually titled “Humanity Part II”) was originally written by Morricone, but was later re-arranged with electronic instrumentation to make it sound more “Carpenter-esque.” I happen to own a version of the soundtrack that includes both Morricone and Carpenter’s material, and it’s my all-time favorite album to play during worship.

I mention this because I find the Thing soundtrack useful for execrations (i.e., hexes or curses that target spiritual rather than human adversaries). In the procedure we’ve used in the LV-426 Tradition, we take some ceramic pots and draw or write things on them to represent our fears and our personal demons. Then we invoke the Serpent into these pots, and we invoke the Red Lord into ourselves. Once a spell against Apep has been recited (with plenty of angry and forceful language), everyone smashes their “qliphothic pot” to bits and pieces, sending the Serpent back to whatever hell it comes from. This is more than just a therapeutic activity for stress relief; it’s a spiritual battle in which we actually smite the negativity in our lives with all of Set’s power and fury. It’s helpful to use music in this kind of worship service, and the Thing soundtrack has always given me the best results. It heightens the effect of the ritual, making me feel as if I’m actually in some desolate wasteland, getting ready to face off against an ancient evil. Even when I listen to the music outside of ritual, it always puts me in a meditative mood, steeling my nerves against whatever stressful crap I happen to be worrying about at the time.

I suppose I’ve rambled on about this movie long enough now. The point is, John Carpenter’s The Thing isn’t just a great sci-fi/horror movie; it’s also a great parable for Setian spirituality. It’s the ultimate cinematic combat myth for the contemporary age, and it is deeply inspirational to me in my own daily quest against the Serpent. It still gets under my skin, too, despite the fact that I’m an adult now and I’ve seen this movie over a thousand times. I still get spooked whenever the power goes out and I have to walk around my house in the middle of the night; I can’t help but imagine the Thing slithering around down there in the dark beneath my bed, waiting to assimilate me in my sleep. There is simply no other movie monster that continues to hold this kind of power over my imagination today, and there are few other films that inspire me as much as The Thing does. If you’re a Setian and you’ve never seen this movie, give it a try as soon as possible, and feel free to share your thoughts about it with me. I’d love to know what you think!