How The Final Conflict (a.k.a. Omen III: The Final Conflict) can be read as an allegory for the Goddess Ishtar and Her rivalry with the spirit of human tyranny.

The Final Conflict (1981)—which was re-christened Omen III: The Final Conflict for its DVD release in the early 2000s—is the second sequel to Richard Donner’s 1976 masterpiece, The Omen. I enjoy the original Omen trilogy in its entirety, but The Final Conflict is the one installment thereof that’s made the largest impression on me. This film also makes me think about the Akkadian Goddess Ishtar, who is one of Set’s many romantic partners and the second-most important deity to me personally.

In case you’ve never seen The Omen or its initial sequel, Damien: Omen II (1978), here is a brief recap of their events. The 1976 original is about a U.S. politician named Robert Thorn (played by Gregory Peck) who learns his child has died while his wife Katherine (Lee Remick) was giving birth. A Catholic priest convinces Thorn to adopt an orphan who was born at the same time at the same hospital. Robert agrees, and the Thorns leave with their newborn baby boy (and with Katherine none the wiser to his true parentage). But as the child, Damien, grows older, weird shit starts to happen. One of his nannies hangs herself in front of his entire birthday party. A new, creepy nanny shows up to take the old one’s place. A crazy priest stalks and harasses Robert. A big black dog starts hanging around the Thorn household. A photographer (David Warner) captures prophetic photos of people’s deaths. And poor Katherine becomes terrified of the child who is supposed to be her offspring. All of which leads Robert to visit Rome, a monastery in Subiaco, and an archaeological dig in the valley of Megiddo, where he learns that Damien is really the son of Satan and can only be killed with these mystical artifacts called the Seven Daggers of Meggido.

What follows is the most disturbingly sympathetic depiction of attempted infanticide that has ever been filmed. Unfortunately, Robert only succeeds in getting himself killed when he tries to prevent the apocalypse (spoilers!), and Damien is then adopted by his uncle Richard (William Holden) in Damien: Omen II. Now an adolescent, Damien (Jonathan Scott-Taylor) remembers nothing of what happened to him or his parents in the first film. He’s also best friends with his cousin Mark, who’s more like a brother to him. Damien and Mark both attend military school, where their drill sergeant (Lance Henriksen) teaches Damien about his true identity. Meanwhile, a nosy reporter tries to convince Uncle Richard of the truth, and this leads to a bunch of increasingly over-the-top deaths. (My favorite is the guy who gets sawed in half by an elevator cable. Truly classic.) Eventually, Damien grows into his predestined role and wipes out all that remains of his family tree so he can be the sole inheritor of the Thorn family fortune.

The Omen is a perfect horror show from start to finish, and it’s every bit as scary as people say it is. The script wastes no time getting down to business, and each of the actors’ performances is Oscar-worthy. But it’s also my least favorite film in the trilogy, for Damien is only a peripheral character in the story. Granted, this is exactly what makes the film so scary; Damien remains completely alien to both his parents and the audience right to the very end, and it’s always easier to be frightened of something when it’s part of the unknown. But I find Damien: Omen II much more interesting, because it’s the first film ever made that actually puts us inside the Antichrist’s head. When Damien learns he is the Great Beast, he’s just as horrified as everyone else is; but the most powerful moment is when his cousin Mark gets wise and confronts Damien about his true identity. Mark threatens to tell everyone, and Damien reluctantly uses his powers to give Mark a brain aneurysm. When Mark drops dead, Damien screams the most convincing scream of despair I’ve ever heard from any character in any movie ever. That scene always makes me weep a little whenever I see it, because Jonathan Scott-Taylor really sells it. Damien: Omen II is quite derivative of the first movie, but it deserves credit for one thing at least: the character of Damien is perfectly written.

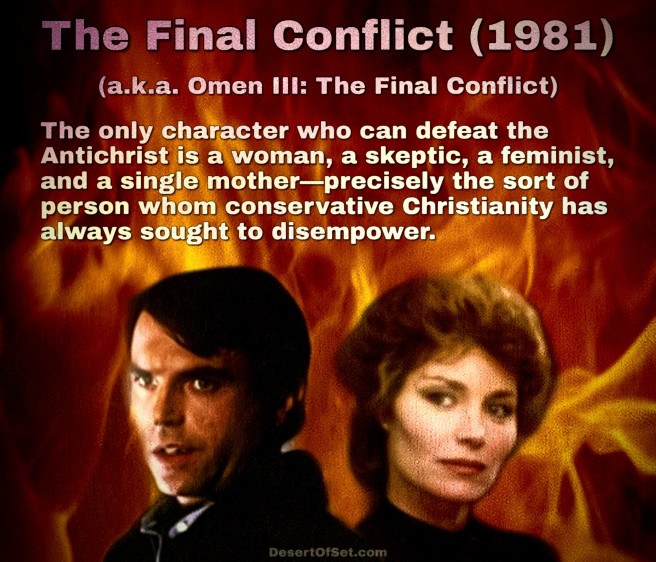

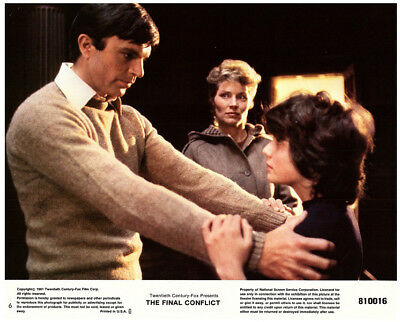

A lobby card for the film.

In The Final Conflict, Damien is now an adult in his thirties, and he’s played by Sam Neill. He has now become the owner of Thorn Industries, a multi-billion dollar company that has revolutionized the food industry, and which is working to solve the world hunger crisis forever. Damien is also the U.S. President’s first choice for Ambassador to Great Britain (after the current guy gets possessed by a black demon dog and blows his brains out). Damien is hot for Great Britain because he has this entirely fictitious apocryphal text called the “Book of Hebron,” which prophesies that Jesus will be reincarnated in Jolly Old England any day now. (Maybe they didn’t have the budget to do a proper Second Coming, with the J-Man flying down from the sky?) But after he sets up shop across the pond, Damien falls for a news reporter named Kate Reynolds (Lisa Harrow); then these Catholic monks at a monastery in Subiaco, Italy find the Seven Daggers of Meggido and try to assassinate him. This leads to a series of hilariously incompetent murder attempts that will have you shaking your head in disbelief. Meanwhile, Jesus is born again somewhere (did you see what I just did there?), but nobody knows where. Lucky for him, Damien knows the birth coincided with a weird astronomical convergence that occurred a few nights ago, so he sends his worshipers out to murder every male baby in England who was born within that time frame. Then Kate Reynolds finds out what the rest of us already know about Damien, and the titular Final Conflict truly begins.

The number one attraction in this film, and the most important reason for anyone to see it, is Sam Neill; he’s literally the greatest Antichrist I’ve ever seen in any film ever. Forget about Michael York, Nick Mancuso, Gordon Currie, or anyone else who’s ever played the Beast in those movies they show on the Trinity Broadcast Network; Sam Neill’s performance here is the gold standard. Rather than playing Damien like some two-dimensional cartoon villain, he plays him like he’s the Gods-damn hero of the movie. He brings so much charisma and charm to the role that he succeeds in making Damien extremely likeable, even when he’s ordering hundreds of newborns to their deaths. Everyone I know who’s ever seen The Final Conflict ends up rooting for Damien somehow (even though they know they’re not supposed to), and they can’t help but feel disappointed with the ending. (More on that in a minute.) The only other performance that’s comparable to this is that of Sir Anthony Hopkins as Dr. Hannibal “the Cannibal” Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). If there is an Antichrist and he ever tries to take over the world, we’d all better pray he isn’t just like Sam Neill in this movie—or else we might actually want him to take over.

The novelization of the 1981 film, The Final Conflict, by Gordon McGill.

In one scene, Damien and Kate walk through a park and see one of the monks, who’s standing on a soapbox, preaching. Damien notices the monk is staring right at him, and he instantly knows the guy is here to kill him. So he starts surveying the area like a hawk—without breathing a word of his concerns to Kate—and he actually looks worried. Is he concerned for himself, or is he concerned for Kate’s safety should there be an ambush? Then there’s another scene where Damien goes to work right after the Christ child has been born. He’s been up all night because he could sense the birth happening, and Kate catches him at the elevator, asking if it’s okay for her to try interviewing him again. (Her last attempt was foiled by another assassin.) Damien smiles and agrees, and she leaves; then he gets in the elevator, sighs, and slumps his shoulders. I’d like to remind you that this character is supposed to be Friedrich Nietzsche’s Übermensch with a vast array of supernatural powers; and yet Neill sneaks in all of these brief human touches—a look of genuine concern, a tired sigh—and actually makes us care about this evil, rotten bastard…

I hate to blow the ending of this film for anyone who hasn’t seen it, but trust me; you probably want to know about this going in. For some reason, I thought this movie was going to end with a big showdown between Damien and Jesus; surely, that would be the “Final Conflict” everyone was expecting, right? I knew things wouldn’t end well for the Beast, but I figured there would at least be some kind of special effects extravaganza. No such luck; the movie ends with Damien being led into a trap by Kate, and Kate stabs him in the back with one of those nifty Meggido daggers. Then Damien limps away, curses Jesus, and promptly dies. Cue music, roll credits. When I first saw this, I was royally pissed. The film had done an excellent job of keeping me at the edge of my seat for the first 90 minutes or so; but it starts running out of steam real fast during the final 20, and that ending just didn’t seem fair. They went through all that hard work of building up this magnificent character and this huge final battle he’s going to have, and what do they give us? Sam Neill getting stabbed in the back (literally) by the woman he loves. I mean, what the hell were they thinking? I wanted to see Damien and Jesus go “Hell in a Cell” on that shit!

An additional lobby card for the film, with Lisa Harrow as “Kate Reynolds” in the center.

But I’ve watched The Final Conflict countless times since that first viewing in 1999, and I think I’ve figured out what they were really going for here. Let’s consider that this film was not made by evangelical Christians with a religious axe to grind; if it had been, they would have kept things as close to their scriptures as possible. Let’s also consider the fact that none of the avowed Christian men in this movie can stop Damien; hell, not even Jesus himself can stop him! The only character who actually poses a real, substantial threat to the Antichrist is (1) a woman, (2) a skeptic, (3) a feminist, and (4) a single mother. In other words, she is precisely the sort of person whom conservative Christianity has always sought to disempower. The real “Final Conflict” here is not between Christ and Satan at all; it’s between male religious violence (perpetuated by Christians and Satanists) and a female secularist who just wants the violence to stop. Note that while Kate scoffs at Christianity at various points in the film, she nevertheless respects its right to exist; and while she eventually sends Damien back to hell, it’s clear she would much rather work things out and share a life with him somehow. Kate is also the only character who commits an act of violence for purely personal reasons. The monks want to kill Damien because he’s the Beast, and Damien wants to kill the Christ child because he’s Jesus; both sides are motivated by purely ideological concerns. But when Kate stabs Damien, it’s because he’s just murdered her son. (Peter is accidentally killed by one of the monks when Damien uses him as a human shield; the poor kid is literally caught between two religious fanatics.) With all this in mind, I now think the climax of this film is far more daring than I originally thought.

I used to think the conclusion to this film was just an example of lazy screenwriting, but I’ve noticed over the years that The Final Conflict gives us several hints about how it will end. In one scene, one of Damien’s “Disciples of the Watch” advises him to stay away from Kate. “I decide who’s dangerous and who isn’t!” Damien shouts angrily, betraying the fact that he feels insecure about Kate himself. Later, Kate falls into a river and almost drowns at Damien’s house. He hesitates before rescuing her (as if he senses that he shouldn’t), but his concern for her overpowers him. As Kate dries herself by the fire back in the house, she tells Damien she feels like a moth who’s flown too close to the flame; she knows he’s dangerous, but she can’t stay away. Damien’s response to her is perhaps the most beautifully-delivered line in the entire film: “Yes—but who is the moth, and who is the flame?” Finally, when Kate stabs Damien at the end with the Megiddo blade, he smiles to himself ever so subtly, as if he’s always known that she would be his undoing. Kate Reynolds was clearly meant to be the savior of humanity in this film from its very conception; and in casting her as such, The Final Conflict offers us a most unexpected soteriology.

“[Damien] is the human son of Satan, fully committed to his Father. But just as Mary Magdalene represented temptation to Jesus, so Kate represents temptation to Damien. She arouses human feelings within him that could so easily lead him astray from his insidious mission, his inglorious destiny.”

—Sam Neill in an 1981 interview upon the film’s release

The hero of this film is an independent, powerful, and successful woman. She isn’t owned or controlled by any man or male divinity. She comes awful close to losing herself in Damien, especially when she spends a dark night of the soul with him in bed. But she rises again from that proverbial pit, stronger than before, and equipped with the power to send her two-faced lover back to the Underworld. Is any of this starting to sound familiar yet? By Gods, it should; for Kate’s arc is basically the Descent of Ishtar all over again. Damien is like a really nasty corruption of Tammuz, a version that’s turned completely rotten. All of his power and wealth are tied to the food industry, just as Tammuz is the God of food and vegetation. But while this “anti-Tammuz” and his enemies are gridlocked in their increasingly futile holy war, Ishtar sneaks in and chooses Her own “messiah” to save the day. The filmmakers try to give Jesus all the credit for this by slapping an obligatory Bible quote on the screen just before the end titles roll; but as far as I’m concerned, it isn’t the Lion of Judah who snuffs the Great Beast here. It’s the Lion of Babylon!

Ishtar be praised!

Contrary to popular wisdom, there is a distinction between “the Antichrist” and “the Great Beast 666” from Revelation 13. Early Christians used the word antichristos to describe anyone who (1) refused Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior, (2) propagated a “heretical” version of Christianity, or (3) claimed to be Christian but didn’t behave like one. The first of these definitions is practically useless since it would seem to include all non-Christians. The second is equally problematic since it requires demonizing all Christian denominations apart from one’s own. The third, however, makes a great deal of sense, for what else can you call someone who claims to love Jesus but fails to treat people in a Christian manner? The real Antichrist has nothing to do with Satanism, but is actually the spirit of Christian hypocrisy itself. Turn on your local televangelist TV network and you will find the true disciples of Antichrist at work, pushing their insane political agendas and extorting millions from their hapless followers in Jesus’ name.

The Great Beast (or Therion in Greek) is based on several ancient kings who persecuted monotheists. People like the Pharaoh in Exodus and the Roman Emperor Nero all had three things in common: (1) they ruled over polytheist nations, (2) they considered themselves to be divine, and (3) they considered the Hebrews and the early Christians to be a threat. After being fed to lions for so long, Christians became convinced that such rulers were actually possessed by Satan himself, and prophetic texts like the book of Revelation were built upon this core concept. While Antichrist represents the evil that lurks within Christianity, the Great Beast represents the archetypal “evil king”—a ruler who tyrannizes his people, and whose actions will bring about destruction and doom. Unlike Antichrist, the Beast doesn’t try to pervert Christianity from within; he seeks instead to destroy it from without. So if we want to get technical about it, Damien Thorn is not really the Antichrist per se, but the spirit of Therion in human form.

Mind you, monotheists have not exactly been “kind” to Pagans throughout history, either. It was especially bad for those civilizations that lived right next door to ancient Israel. The Gods and Goddesses of these cultures are specifically named as “demons” in the Old Testament (e.g., Ba’al, Asherah, etc.) and are commonly invoked as such in contemporary media. Lady Ishtar is just one of these divinities, and it’s sad to think that whenever She is discussed in today’s world, it is almost always in terms of biblical prophecy. She is even linked with Therion in the book of Revelation:

Then the angel said to me, “The waters you saw, where the prostitute sits, are peoples, multitudes, nations and languages. The beast and the ten horns you saw will hate the prostitute. They will bring her to ruin and leave her naked; they will eat her flesh and burn her with fire. For [Yahweh] has put it into their hearts to accomplish his purpose by agreeing to hand over to the beast their royal authority, until [Yahweh]’s words are fulfilled. The woman you saw is the great city that rules over the kings of the earth.”

—Revelation 17:15–18

As I’ve discussed before, the Whore of Babylon is clearly inspired by Ishtar, even if her symbolic purpose is different. But what I find especially interesting here is the contrast between a female entity who “rules over the kings of the earth” and an evil king who has turned against her. Ishtar presides over the concept of “sacred kingship,” which required a Babylonian king to “marry” the Goddess and serve the people as Her priest. He had to ensure that his nation’s crops didn’t fail, that his borders remained protected from foreign invaders, and that his people were cared for in times of disaster. He also had to perform religious rituals all the time to ensure that his people’s Gods were properly appeased. A lousy ruler who brought ruin to his people would have been considered “unfaithful” to Ishtar, and some kings were even sacrificed to atone for this sin. This only reinforces my opinion that by killing Damien in The Final Conflict, Kate Reynolds is actually sacrificing him to Ishtar as penance for his disastrous leadership. (It’s reassuring to think that with the Queen of Heaven, even monarchs can be held accountable and taken to task.)

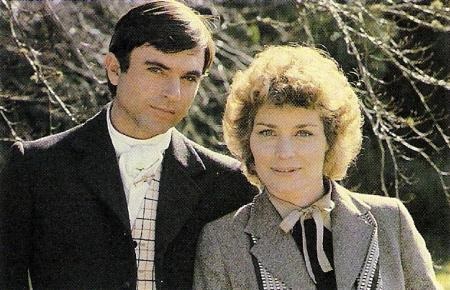

Sam Neill and Lisa Harrow posing for a behind-the-scenes photo.

Don’t get me wrong; The Final Conflict is not a perfect film. There are times when it sabotages itself by trying to copy the original Omen too much. Why are we still wasting time with lone individuals getting slaughtered in isolated places? Why isn’t Damien the President already when this film begins, sending troops to invade the Middle East and start World War III? They missed an opportunity to enlarge the scale and the stakes of the story here; and by restricting all the action to Great Britain, they do a great injustice to the premise. The only exception to this is the baby-killing conspiracy sequence, which is one of the most chilling things I’ve ever seen. The murders themselves are never shown, but are only suggested through quick cuts, musical cues, and horrified reactions from the actors. This is a perfect example of how the power of suggestion can leave a much deeper impression on the mind than just painting the screen with gore. It also helps keep the violence as tasteful as possible (which is no small feat, considering the subject matter), while also making it more disturbing to sit through. If you think the jump scares in The Conjuring (2013) are scary, try watching the scene where one of Damien’s disciples—an Anglican priest—gives a newborn his own version of a “baptismal rite.” It makes my skin crawl just thinking about it.