Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982) is my second-favorite movie of all time, right after the original Halloween from 1978. Though it is marketed as a “sequel” to the latter film, it is really something completely different. It has nothing to do with Michael Myers, Laurie Strode, Dr. Loomis, or the town of Haddonfield, Illinois at all. By gods, it isn’t even a “slasher movie,” but something more like a British sci-fi/folk horror hybrid!

Season of the Witch is the story of Dr. Dan Challis (played by Tom Atkins) and Ellie Grimbridge (Stacey Nelkin), who decide to investigate a brutal murder their local police have chosen to ignore. In doing so, Dan and Ellie stumble upon a ghoulish plot masterminded by the one and only Conal Cochran (Dan O’Herlihy), founder and CEO of a major toy-manufacturing company called Silver Shamrock Novelties.

It turns out that Silver Shamrock, Inc. has stolen one of those monolithic rocks from Stonehenge and broken it down into countless microscopic pieces. They have inserted this debris into their world-famous Halloween masks, which children across the nation are buying in droves. They’ve also developed a TV commercial with a flashing “magic pumpkin” that activates the pieces of Stonehenge within the masks. This converts the masks into deadly cursed talismans, which transform their wearers into snakes and bugs (from the inside out!). Even crazier, most of Silver Shamrock’s employees appear to be killer androids with superhuman strength, and Cochran’s entire conspiracy is somehow tied to the fact that the planets of our solar system are currently in alignment.

You’re probably wondering why Halloween III has nothing to do with any of the other Halloween films. When John Carpenter and Debra Hill were approached for another sequel following the box office success of Halloween II (1981), they took the opportunity to conduct a most fascinating cinematic experiment. Starting with Halloween III, the series would now be an anthology like The Twilight Zone, featuring a different Samhain-themed story with each new installment. There are so many different things that we associate with October 31, including ghosts, witches, fairies, and druids; why then should a franchise called Halloween be limited to just an escaped spree killer?

Tom Atkins, who plays Dr. Challis, is what they call a “character actor.” This means he usually plays supportive roles and is more or less the exact same character in each one. To this day, Season of the Witch is still the only film in which he ever got to be the leading man.

We usually expect our male sci-fi/horror protagonists to be young, dashing, and athletic; but Dr. Challis is middle-aged, visibly tired, and very much out of shape. He apparently lives and sleeps at the hospital where he works, and he is a divorced alcoholic who can’t stand his ex-wife or his kids (and who seems to have a history of avoiding them whenever possible). Given a choice between (1) spending time with his estranged children or (2) investigating a murder mystery with some hot young lady he barely knows, he doesn’t even stop to think about it; he chooses the second option immediately. But despite all his faults, Challis is anything but reprehensible. Whatever else he might be, he is a doctor from first to last, and he takes this role very seriously. He is all about making people better, and when the chips are down, he does everything he can to save the world (including his family).

Tom Atkins might not be a Christopher Lee or a Peter Cushing, but he really shines in this role. If you enjoy his performance here as much as I do, check out Night of the Creeps (1986). He plays Detective Cameron, an alcoholic cop whose girlfriend was butchered by a serial killer back in the 1950s. When Creeps begins, Cameron is on the verge of killing himself; but when he learns his town is being invaded by brain-eating slugs from outer space, he grabs a shotgun and starts blowing holes in everybody else instead!

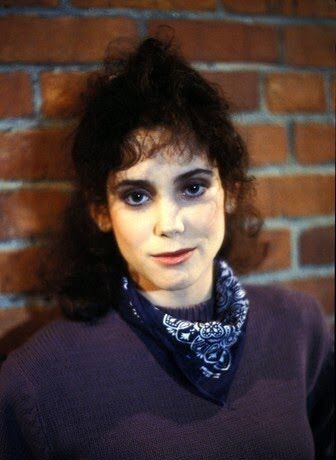

Ellie Grimbridge, played by Stacey Nelkin, seems to prefer older men; she takes a liking to Dr. Challis almost immediately, and as soon as they reach that motel in the mysterious little town of Santa Mira (where Silver Shamrock’s headquarters is located), she is all over him. Later, Ellie is kidnapped by Conal Cochran’s robot goons, and she is imprisoned somewhere in the Silver Shamrock factory. Challis busts in to rescue her, getting himself captured in the process. Then he learns the truth about Cochran’s dastardly scheme, escapes and finds Ellie, and torches the factory. Challis and Ellie drive off into the night, trying to plan how they can stop that crazy Silver Shamrock commercial from playing on TV and causing the apocalypse—

—and that’s when Ellie suddenly tries to kill Challis, revealing herself to be a goddamn robot!

Fans are divided as to whether Ellie is (1) human for most of the film (and replaced with a robot duplicate by Cochran during the final act), or (2) a robot the entire time. It makes no sense to me why Cochran would send a robot to seduce Challis into investigating his own damn conspiracy; but the idea of not knowing you’re sleeping with a killer robot is pretty disturbing. All I know for sure is, this sequence scared me really badly when I first saw it as a kid. To think you’ve just rescued someone you love, only to learn they’ve been replaced with a soulless imitation that wants to destroy you? That’s Grade-A nightmare fuel for me, right there!

Stacey Nelkin was also cast to play the sixth Nexus-6 replicant in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which was released the same year. Her part was cut from that film during principal photography due to budget cuts. (Blade Runner fans will recall that in at least one version of the film, Captain Bryant recruits Deckard to track down six fugitive replicants; yet there are only five that are accounted for in the entire film, and this is why.) It’s eerie to think that Nelkin was cast to play two murderous androids in two different films during the same year, huh?

Conal Cochran, Halloween III‘s antagonist, is played by Dan O’Herlihy, an Irish actor of such stature that one wonders just how the hell anyone convinced him to do this movie. Unlike Tom Atkins, O’Herlihy was used to acting in things like Orson Welles’ version of Macbeth (1948), Luis Bunuel’s Robinson Crusoe (1954), and Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo (1970). He even went toe-to-toe against Marlon Brando at the Academy Awards once. (Brando won, but O’Herlihy gave him a run for his money!) Considering Halloween III’s budget, I highly doubt O’Herlihy was paid very much for his work. So what the hell was it about Season of the Witch that made this legendary thespian say, “All right, I’ll do it”?

Debra Hill once recounted that Dan O’Herlihy knew an awful lot about the true origins of Halloween . He told all kinds of folk stories about Samhain to the rest of the film’s cast and crew. These stories were apparently so enthralling that everyone took to calling O’Herlihy “Mister Halloween.” It’s unfortunate that Hill couldn’t recall any specifics from these conversations, but I can certainly imagine what they must have been like. After all, Halloween III is one of very few flicks ever made in which the word Samhain is pronounced correctly, and it is O’Herlihy himself who pronounces it in his native Gaelic tongue.

I have a hunch that Dan O’Herlihy was primarily interested in Halloween III for its references to Irish culture. Considering the long list of films in which he has appeared, it’s interesting to note that almost none of them have anything to do with Ireland (either culturally, historically, mythically, etc.). I sense this man was really proud of his heritage, and that when his agent handed him the script to Halloween III, he recognized the project as an opportunity to finally represent that heritage onscreen somehow.

The original screenplay for Halloween III was written by Nigel Kneale, creator of the British Quatermass films and TV serials. The first draft included a great deal more science fiction than the finished film does. Conal Cochran turns out to be some kind of daemon or alien; he simply impersonates a human being with his mask-manufacturing know-how. He also transports the monolith from Stonehenge to America by interdimensional means, and there is plenty more speculation as to what Stonehenge is actually made of (and why it becomes so volatile whenever the planets are aligned). More of Cochran’s genocidal plan is explained, as well. John Carpenter and director Tommy Lee Wallace both felt that some of this material wouldn’t translate very well for American audiences, so they took turns re-writing the script to “Americanize” it a little. This led Nigel Kneale to demand that his name be removed from the credits; but it seems to me that his original ideas are still present (and mostly intact) in the film.

In 1979’s The Quatermass Conclusion, Stonehenge and other prehistoric places are revealed to be “landing sites” for a hostile alien force. It is difficult to be certain without reading Kneale’s original script, but it seems plausible to me that Season of the Witch and The Quatermass Conclusion were meant to be thematically linked in some way. The Quatermass serials also had a direct influence on Doctor Who, which explores many similar ideas and themes. Perhaps it is no accident, then, that Conal Cochran resembles a classic Doctor Who villain like Davros, the Master, or even the Black Guardian. I can totally see him as an evil renegade Time Lord, disguised as an Irishman.

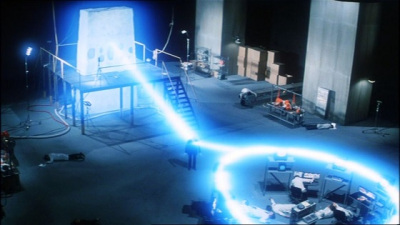

Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law states that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” and the scene when Cochran explains his plot to Dr. Challis is a great example. “Advanced…” he says, pointing to a room full of computers, “…and ancient technology,” he finishes, pointing to the monolith he has stolen from Stonehenge. His machines are all arranged in a large circle formation that’s clearly modeled on Stonehenge; a visual hint that the original monument might be some kind of ancient “supercomputer” itself. The implications of this are staggering; who or what built this prehistoric machine, and for what purpose? Halloween III never answers these questions, but I suspect Cochran knows. And if just one piece of this “supercomputer” is sufficient to devastate the entire North American continent in one fell swoop, what the hell would happen if all of Stonehenge were suddenly “switched on?”

At the end of the film, Conal Cochran is zapped by a big blue laser that shoots out from the stolen (and newly re-activated) Stonehenge monolith. When this happens, Cochran’s features are momentarily distorted, as if his face were really just a mask. Then he vanishes into thin air, never to be seen again. Many viewers assume this to be Cochran’s “death scene,” but I beg to differ. The Halloween III novelization by Dennis Etchinson (writing as “Jack Martin”) makes it clear that this moment in the story is really just the beginning of Cochran’s evil. It also goes into detail on how Cochran isn’t just a crazy toymaker, but something that transcends time and space as we tend to understand such things.

Here’s a snippet from the novel, in which Dr. Challis considers Cochran’s true cosmic nature:

Cochran was nothing new, whatever his latest disguise. He and the dark forces he represented had been around in one form or another since the beginning of time; there was no good reason to believe something so ancient had really been destroyed in a blaze of fireworks in a small town on a cold autumn night. This year’s dark venture was like a rerun on the Late, Late, Very Late Show, an endless loop re-enacting the last reels of the same relentless stalking of the heart of the American dream. It had always been so…He would come to movie theaters and TV screens over and over in untiring replays for as long as people turned away and pretended he was not really there; for that very refusal gave him unopposed entrance to their innermost lives. Nothing ever stopped his coming and nothing ever would stop it, not for as long as people deferred the issue of his existence to the realm of fantasy fiction, that elaborate system of popular mythology which provided the essence of his access…For now, he was still advancing, merely shifting from one field of view to another, larger one, from a single television screen to the televised psyches of a nation. Challis shuddered.

Before he pulls his disappearing trick, Cochran says “we” a lot. This suggests that he actually has peers; yet no one who works for him at Silver Shamrock seems to really qualify as such (especially since most or all of his employees are robots, anyway). Cochran’s “we” must therefore be referring to some other group of peers whom we never get to see. He also mentions “those who came before” him, and he speaks of human beings as if he thinks we’re all insects. It seems clear to me, at any rate, that Conal Cochran is not a “human being” at all, but some preternatural creature that has been visiting our world since ancient times. This is sustained not only by the novelization, but by what is known about the Nigel Kneale script as well. In fact, I suspect Conal Cochran is actually what Celtic folklore calls a “Fae of the Unseelie Court.”

The popular image of fairies as “cute little Tinkerbells” is utter horseshit. The oldest stories depict these creatures as being much darker and more sinister than any Disney movie would have us believe. Celtic folklore is full of benign fae who are willing to live in balance with their human friends and neighbors; but it’s also full of malevolent fae (the “Unseelie Court”) who just want to commit horrific atrocities, like kidnapping babies or tricking people into cannibalizing each other. These entities can make themselves look like anything as well, including animals, trees, furniture…or even Dan O’Herlihy!

Wearing masks for Halloween started as an apotropaic ritual for keeping the unseelie fae away. But as Cochran notes in Season of the Witch, people today think “no further than the strange custom of having [our] children wear masks and go begging for candy.” He says “the last great” Samhain was over 2,000 years ago, “when the hills ran red with the blood of animals and children.” This is curious, given that Irish people have been observing Samhain each year right into modern times. There is also a historical discrepancy in Cochran’s claim, since the first recorded literary references to Samhain date back to the 10th century CE (which was only 1,000 years ago). We know the Celts did not sacrifice children or animals like that, either; so what is Cochran really talking about here?

If you ask me, Conal Cochran was actually there in Ireland 2,000 years ago; he and his fellow unseelies roamed the land, murdering children; and he was probably what motivated the druids to develop their Samhain traditions in the first place. This would explain why there hasn’t been an October 31 to Cochran’s liking for 2,000 years; all that quality Halloween magic was just too strong for evil creatures like him to stomach. But now that it’s 1982 and Halloween has been completely trivialized, the magic is no longer effective. Now unseelie fae like Cochran can intrude upon the mortal realm as much as they please, and they can even weaponize the things that once kept us safe, as Cochran does with his deadly Silver Shamrock masks.

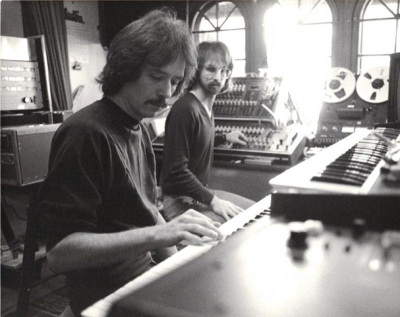

While John Carpenter neither wrote nor directed Halloween III himself, he did score the music. His partner in crime on this task was Alan Howarth, a Hollywood sound designer who co-wrote most of Carpenter’s 1980s film scores, including: Escape From New York (1981), Halloween II (1981), Christine (1983), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Prince of Darkness (1987), They Live (1982), and the incidental music for The Thing (1982). Howarth also scored Halloween 4 (1988), Halloween 5 (1989), and Halloween 6 (1995) by himself, weaving Carpenter’s familiar 5/4-time piano melody into some truly impressive soundscapes of his own.

Carpenter and Howarth were an excellent team; I enjoy listening to their music by itself as much I enjoy watching the films for which it was all composed, and Season of the Witch boasts some of their very best work together. Since the entire point was to break away from the first two movies, the aforementioned 5/4 piano theme is nowhere to be heard (except whenever Halloween III’s characters happen to catch a glimpse of the first Halloween on TV!). We are instead given a host of new original tunes, all performed on classic Moog synthesizers and sequencers. “Chariots of Pumpkins” might well be considered the main Halloween III theme, and it is one of my favorite pieces of music ever written.

So given its fascinating plot, terrific performances, and outstanding musical score, why on earth did Halloween III: Season of the Witch tank in theaters?

Well, it’s all about marketing. Though John Carpenter and Debra Hill tried to make their creative intentions very clear, this information was only relayed to the general public by publications like Fangoria magazine. Considering that Fangoria didn’t have half the fanbase in 1982 that it has today, this meant that Carpenter and Hill’s plan went completely unnoticed by most audiences. At the same time, Universal Pictures found the notion of a “Shape-less” Halloween unsettling, and their advertising department actually tried to hide the fact that Halloween III would be different. Nothing about the new artistic direction was mentioned in any trailers or TV commercials for the film. As a result, most audiences in October 1982 were basically walking into the movie blind.

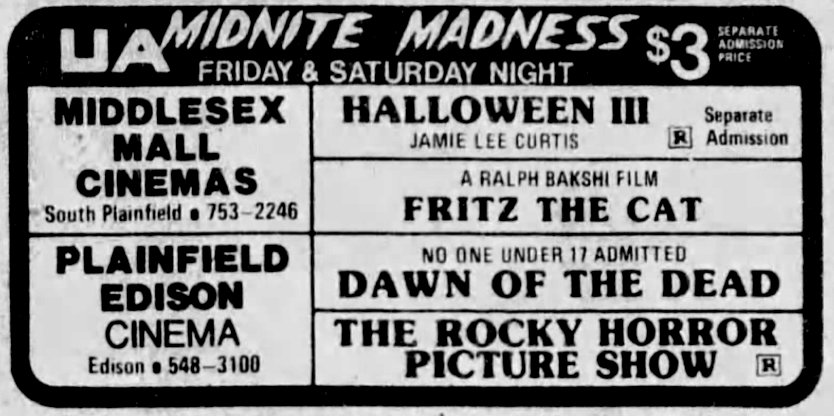

In my experience at least, people who prefer slasher movies usually don’t “get” other kinds of horror, and viewers who prefer other subgenres tend to find slashers distasteful. So on the one hand, every slasher fan in the world went to see Halloween III and was greatly disappointed; on the other, fans of other subgenres avoided the film precisely because they thought it would be a slasher. An entire decade would pass before Season of the Witch finally started finding its audience on VHS and during late night monster movie marathons.

I first saw Season of the Witch in 1995. I understood it would not be a slasher film going in, but I think I was probably expecting something more like Stan Winston’s Pumpkinhead (1988), with old crones conjuring medieval hellbeasts out in the woods. I sure as fuck wasn’t expecting to see some alien Pied Piper, turning children into creepy crawlies with his maleficent merchandise, his android assassins, and his Stonehenge supercomputers. This was all WAY too much for my 13-year-old brain to process in just one viewing. The whole thing was somehow ludicrous and terrifying at the same time, and it kept me awake at night for weeks.

The scene where Conal Cochran mentions the Festival of Samhain was a complete mystery to me at first. It wasn’t until I re-watched the film with subtitles that I realized he is even talking about Samhain, because I didn’t yet know the correct pronunciation of this term. In reading up about Samhain in real life, I learned that people still celebrate it today, including many Pagans. It would be a couple more years before I learned about Setians, but Season of the Witch facilitated my awareness that there is even a Pagan community in general at all. And while I’ve never felt drawn to the Celtic pantheon in any religious capacity, Samhain or Hallowtide has always been a huge deal to me. So in a weird way, Halloween III didn’t just expand my mind on how people can tell stories; it expanded my mind on how people can believe and live their faith, as well.

I consider Halloween III: Season of the Witch to be the absolute best follow-up to the original Halloween (1978) that has ever been made, and it is unlikely to ever be superceded in this respect. None of the sequels or remakes with Michael Myers can hold a candle to it, because even the best of them are essentially just copies of the first movie, a story that was never meant to be continued in the first place. And while the Myers follow-ups have each been motivated primarily by box office avarice, Season of the Witch is a unique and original story that demanded to be told, much like its thematic predecessor from 1978. John Carpenter and Debra Hill’s pitch for an anthology is equally interesting, but I think it would have been neat to see Conal Cochran a few more times before Dan O’Herlihy passed away in 2005. One reason I love the Halloween movies as much as I do is because this series features not one, but two of the scariest horror movie supervillains I have ever seen. Only one of them visibly wears a mask and stalks people, stabbing them with kitchen utensils. The other one wears a much less obvious mask—a handsome human smile—and tricks people into purchasing their own deaths.