Some background on the unique Setian coven in which I became a priest.

There are three other Setians with whom I’ve been privileged to work some truly life-changing magic over the years. These individuals know who they are, but out of respect for their privacy, I will only identify them here as Blackwyn, the Tonester, and Sister Bean. To walk with Set is a solitary path, even when you’re part of a group, and not everyone in my circle will always agree with each other on everything. But the point isn’t that we always believe or practice the same things. The point is that we are each drawn to Set in our own ways and for our own reasons; that we’ve crafted a number of effective rituals and spells together; and that we’ve all witnessed the same eerie results these procedures can yield. Years have passed since we first declared ourselves a coven back in 2003; we’re spread far apart from each other now, living in our own areas and focusing on our own priorities. But even if we never meet in person to hold another ritual together again, we will always be connected with each other somehow.

That “somehow” is Set.

In 2007, we started referring to our collected rites as the LV-426 Tradition for the following reasons:

- The 1979 sci-fi/horror film Alien is a prime example of what we call “the monster film as mythos,” and we wanted our name to memorialize the film for this reason.

- The Tonester and I were both living in the Bible Belt at the time, and Ripley’s struggle against the Alien was a perfect metaphor for how we felt about living there.

- Being a couple of smartasses, we wanted a name that was far too cumbersome for repeated use in brief conversation. (Say “LV-426 Tradition” six times in the same paragraph to see what I mean!)

From left to right: The Tonester, Sister Bean, Yours Truly, and Blackwyn.

In case you’ve never seen it (and shame on you if you haven’t!), the original Alien is about these astronauts in the distant future who follow what seems to be a distress signal of unknown origin. They make their way to a desolate planet called “LV-426” in their star charts, where they find a crashed alien spaceship with a dead crew and a shit-ton of weird, leathery eggs for its cargo. One of these eggs hatches, unleashing a horrific beast that reproduces itself by raping one of the men (!). Due to a breach in protocol, the creature enters the next phase of its life cycle back on board the ship, and the movie then becomes a slasher flick in outer space. The last person standing is Ellen Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver, who emerges from the chaos and the carnage to become the first female action movie hero.

The Alien strongly resembles Apep, that timeless arch-nemesis of Set. Designed by the Swiss surrealist, H.R. Giger, its biology makes no sense. How can it see without any eyes? Why would anything evolve to have two mouths—one inside the other—when just one mouth is simpler? How can its blood be so corrosive that it will burn through any metal, but without being deadly to the creature itself?1 Nothing in nature can exist like that, and the same is true of Apep. It’s described as lacking any sensory organs—it has neither eyes nor ears—yet it’s somehow able to locate and paralyze its prey with a hypnotic gaze. It’s also described as “breathing by means of its own roar” and “living by means of its cries,” which means it doesn’t require any sustenance for its survival; it just eats things to make them suffer (Manassa, 2014). Both Apep and the Alien are monsters that can only exist in nightmares, that operate in total defiance of natural law, and that would be absolutely poisonous to any ecosystem in which they managed to thrive.

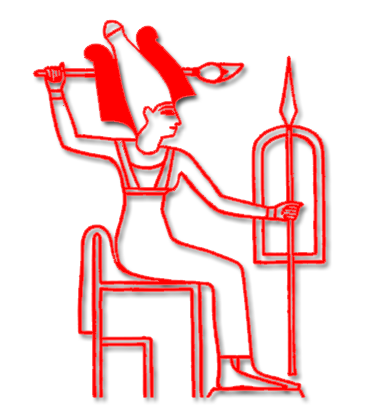

Ellen Ripley, on the other hand, is a perfect stand-in for the Red Lord. She is the outsider or “black sheep” among her crew, the only one who takes her job seriously, and a real stickler for protocol (even refusing to let Captain Dallas [Tom Skerritt] board their ship when she learns he has an infected crew member in tow). Compare this to the other female crew member, Lambert (played by Veronica Cartwright), who complains, screams, or cries helplessly throughout the film. Then there’s the fact that Ripley dresses and behaves like a man. One of Set’s many lovers is the Ugaritic Goddess Anat, who is usually depicted in men’s clothes (Patai, 1990), and whom Set is said to find especially attractive for this reason. Given how much He enjoys smiting monsters like the xenomorph, and given how partial He is to androgynous ladies like Anat, it’s hard for me not to imagine Set cheering for Ripley from upon His throne behind the Great Bear. (Plus, going through so much trouble to save Jones the Cat must surely score Ripley some additional points with Bast, Ishtar, Sekhmet, and other like-minded Goddesses of feline goodness.)2

Anat, an Ugaritic Goddess who is one of Set’s many consorts.

Alien is also filled with various references to sexual anatomy and the reproductive process. The ship’s computer is called “Mother”; the astronauts look like they’re being born when they awaken from their cryogenic sleep chambers; the tunnels of the derelict craft on LV-426 resemble giant fallopian tubes; and the xenomorph’s head is shaped like an erect penis (which always makes me think of someone being raped in reverse during the infamous “chestburster” scene).3 Ripley even has her final confrontation with the beast in her underwear,4 and she must also contend with “Mother,” which insists on keeping the Alien alive for future study (even at the cost of the astronauts’ lives). So a secondary conflict rages between Ripley and the computer, which cares more for the survival of the “child” than it does for the “parents.” This is especially intriguing given that Set is thought to cause abortions and miscarriages (te Velde, 1977). As His cinematic avatar, Ripley must further alienate herself from her society by “aborting” the gestating life form her superiors have deemed more important than herself (Cobbs, 1990).

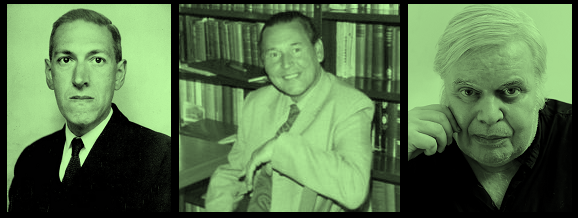

H.R. Giger was obviously influenced by the New England horror writer, H.P. Lovecraft; but I’m fairly certain he was also inspired by a British occultist named Kenneth Grant. Once a disciple of the infamous Aleister Crowley, Grant was obsessed with what he called the “Tunnels of Set,” which are supposed to be these astral wormholes that loop back and forth between various alternate universes. He was the first occult author to suggest that H.P. Lovecraft was a “sleeping prophet,” and that monsters like Cthulhu and Nyarlathotep are real beings that actually exist in some other dimension. (He beat the Simon Necronomicon to this punch by at least a decade, if not longer.) Given this, I’m sure Grant’s ajna chakra or “third eye” probably exploded wide open if and when he ever got around to seeing Alien for himself. And if H.R. Giger wasn’t specifically thinking about the “Tunnels of Set” when he first envisioned the winding, cyclopean corridors of that ghost ship on LV-426, he sure as hell could have fooled me.

From left to right: H.P. Lovecraft (1890–1937), Kenneth Grant (1924–2011), and H.R. Giger (1940–2014).

Though we tend to share Grant’s enthusiasm for the “many-worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics, my coven mates and I have zero interest in contacting any of the horrific fauna that H.P. Lovecraft envisioned for his lurid tales. We instead emphasize execration, or the use of magic to repel negativity and misfortune from people’s lives. This is functionally similar in principle to casting a death curse on someone, save that the target of your spell is Apep, the true source of all evil, and not any human victim. As far as we’re concerned, walking with Set isn’t about getting chummy with Lovecraftian space monsters; it’s about ferociously defending the autonomy of all sentient beings.

The idea that we must be “ferocious” in this regard comes from when the Tonester and I lived in the Bible Belt during the early 2000s. We were constantly under siege from “Rapture-ready” teachers, classmates, employers, cops, and politicians. We couldn’t even go for prayer walks in the woods without being harassed by people who thought we were “worshiping the devil.” After a while, it began to feel as if we were actually trapped in some hostile wilderness, with a very real monster coming after us. That monster wasn’t an actual xenomorph, of course, but Apep; and instead of literally trying to eat us, it was trying to eat our hearts from within. But Set is merciful; He brought us together in that wretched place, against all odds, and He blessed us with each other’s company and support. Then we met Blackwyn and Sister Bean in Michigan a few years later, and the rest is history. Each of us is proof for the others of Set’s providence, and Alien is an excellent parable for our own private quests against the Serpent.

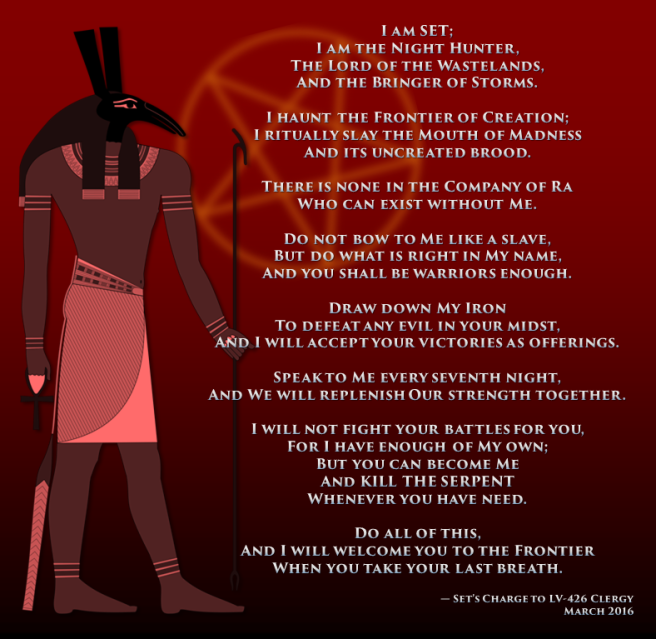

But execrations are not the only staple of our practice; there’s also our weekly Sabbat ritual, which is observed on Friday nights. We enter a darkened room that has been prepared with an altar, an image of Set, and some red candles. We recite our standard invocation together, and then we take turns praying to Set informally, as if He were just a regular person in the room with us. Usually this means discussing our hopes and fears, our best and/or worst moments of the week, or something along those lines. When one person finishes their prayer, they turn to the next person in sequence (which is always to the left) and say, “If there is anything you wish to say to the Red Lord at this time, please feel free to do so.” And if the next person has nothing they wish to pray about, they keep silent so the next person can proceed. Once everyone has finished, we break out the beer, blast some heavy metal, and chat with each other into the wee hours, sometimes not adjourning until daybreak. The exchanges we’ve shared during these late night Sabbat talks are some of the most profound meditations I’ve ever experienced in my life.

Some other things we’ve done include a spell for protection during sleep, an astral pilgrimage technique, and a matrimonial ceremony that was used for my wedding in 2012 and for Sister Bean’s in 2015. There’s also an initiation ritual that’s used for inducting new members, but this procedure is known only to those who pass our vetting process and are invited to join. (Considering there have only been four of us since Set first struck me with His black lightning in 1997, you can imagine how often this happens.) Our liturgical calendar includes not only our weekly Sabbat but also Hallowtide (October 31–November 2), Walpurgisnacht (April 30), and Friday the Thirteenth (on which we celebrate Set as the catalyst for Osiris’ resurrection and Horus’ conception). Importantly, we have no leader or “high priest/ess”; each of us is fully qualified to administer our rites to anyone who might need them, and all of our group decisions (including whether to initiate any new brothers and/or sisters) are made by unanimous vote.

Apart from the above, we Setians of the LV-426 Tradition may each entertain any additional beliefs or practices we like. Some of us revere other sacred figures along with Set, like Buddha, the Norse God Odin, or the Babylonian Goddess Ishtar. Some of us even celebrate Christmas or Saint Patrick’s Day. Our eclecticism is rooted in Set’s New Kingdom role as an ambassador between the Egyptian Gods and other pantheons. Just as He can roam between alternate realities and canoodle with alien divinities, so are we free to mix the old Kemetic wisdom with just about anything we find useful, from American colonial witch lore to Zoroastrian demonology. Some outsiders may find this permissiveness toward religious dogma repugnant, but we couldn’t care less; Big Red is the only justification we need.

It’s been a while since we last met as a coven to keep the Sabbat, execrate our inner demons on Walpurgisnacht, or offer up a feast of watermelon to Big Red on Friday the Thirteenth. I can’t speak to how often the others may or may not “keep up” with these practices nowadays (though I must admit it has been hard for me to do so consistently, myself), but none of us has ever been expected to make such a commitment anyway. It’s the fact that we even did these things at all—and the magic we shared when we did—that really matters. And there’s always the possibility that somewhere down the road, a fifth initiate of LV-426 might present him or herself to us, setting a whole new cycle of ritual work into motion. For now, all LV-426 alumni are off exploring other proverbial worlds, but always with Set’s Iron in our spines.

The LV-426 Sigil

Notes

1 I’m well aware that in Ridley Scott’s prequels to this film—Prometheus (2012) and Alien: Covenant (2017)—it’s revealed that the xenomorphs did not evolve naturally, but were genetically engineered as a kind of biological warfare. This still doesn’t explain why their blood, which can burn through any damn metal you please, doesn’t just burn right through their own bodies as well.

2 Some viewers—including Big Steve King—complain that Ripley’s quest to save Jones the Cat is a “sexist interlude” that undermines her role as a feminist character (King, 1983). I’m a proud cat parent, and if I were in Ripley’s position, I’d risk everything to save my fur baby too. (Ten bucks says if Jones were a dog, nobody would be bitching about this.)

3 The “chestburster” scene is quite similar to the story of Set’s birth according to Plutarch (1970). He recounts that Set was not born at the normal time or in the normal fashion, but that He impatiently exploded forth from the belly of His mother, the sky Goddess Nut. It’s tempting to think the screenwriter, Dan O’Bannon, might have encountered this story at some point while writing the script for Alien.

4 Some viewers—again, including Mr. King—complain that this final sequence “sexualizes” Ripley too much (King, 1983). I have to say that as a straight dude, this scene has never once made me think, “Ooooh, look at the naked chick!” Instead, it always makes me think about this one time I had to fumble around in my basement naked to get some clean clothes out of the dryer, only to be greeted by a huge spider that made me piss myself. In other words, it makes me identify with Ripley rather than objectify her, and I for one applaud Ridley Scott for framing the scene in that way.

References

Cobbs, J.L. (1990). Alien as an abortion parable. Literature / Film Quarterly, 18(3), 198–201. Retrieved on October 5, 2017.

King, S. (1983). Danse macabre (2nd edition). New York, NY: Berkley Books.

Manassa, C. (2014). Soundscapes in ancient Egyptian literature and religion. In E. Meyer-Dietrich (Ed.), Laut und leise: Der gebrauch von stimme und klang in historischen kulturen (pp. 147–172). Bielefield, Germany: Transcript Verlag.

Patai, R. (1990). The Hebrew Goddess (3rd edition). Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Plutarch (1970). De Iside de Osiride. Cardiff, Wales: University of Wales.

te Velde, H. (1977). Seth, God of confusion: A study of His role in Egyptian mythology and religion. Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill.